There’s an apocryphal quote floating around the internet that “640K ought to be enough memory for anybody” but it does seem unlikely that this was ever actually said by any famous computer moguls of the 1980s. What is true, however, is that in general more computer memory tends to be better than less. In fact, this was the basis for the Macintosh 512k in the 1980s, whose main feature was that it was essentially the same machine as the Macintosh 128k, but with quadruple the memory as its predecessor. If you have yet to upgrade to the 512k, though, it might be best to take a look at this memory upgrade instead.

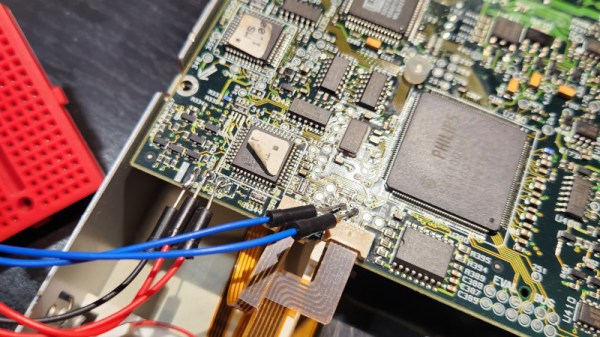

The Fat Mac Switcher, as it is called by its creator [Kay Koba], can upgrade the memory capability of these retro Apple machines with the simple push of a switch. The switch and controller logic sit on a separate PCB that needs to be installed into the computer’s motherboard in place of some of the existing circuitry. The computer itself needs its 16 memory modules replaced with 41256 DRAM modules for this to work properly though, but once its installed it can switch seamlessly between 512k and 128k modes.

Another interesting quirk of the retro Macintosh scene is that the technically inferior 128k models tend to be valued higher than the more capable 512k versions, despite being nearly identical otherwise. There are also some other interesting discussions on one of the forum posts about this build as well. This module can also be used in reverse; by installing it in a Macintosh 512k the computer can be downgraded to the original Macintosh 128k. For this the memory modules won’t need to be upgraded but a different change to the motherboard is required.

A product like this certainly would have been a welcome addition in the mid 80s when these machines were first introduced, since the 512k was released only months after the 128k machines were, but the retrocomputing enthusiasts should still get some use out of this device and be more able to explore the differences between the two computers. If you never were able to experience one of these “original” Macintosh computers in their heyday, check out this fully-functional one-third scale replica.