Security assumes there is something we can trust; a computer encrypting something is assumed to be trustworthy, and the computer doing the decrypting is assumed to be trustworthy. This is the only logical mindset for anyone concerned about security – you don’t have to worry about all the routers handling your data on the Internet, eavesdroppers, or really anything else. Security breaks down when you can’t trust the computer doing the encryption. Such is the case today. We can’t trust our computers.

In a talk at this year’s Chaos Computer Congress, [Joanna Rutkowska] covered the last few decades of security on computers – Tor, OpenVPN, SSH, and the like. These are, by definition, meaningless if you cannot trust the operating system. Over the last few years, [Joanna] has been working on a solution to this in the Qubes OS project, but everything is built on silicon, and if you can’t trust the hardware, you can’t trust anything.

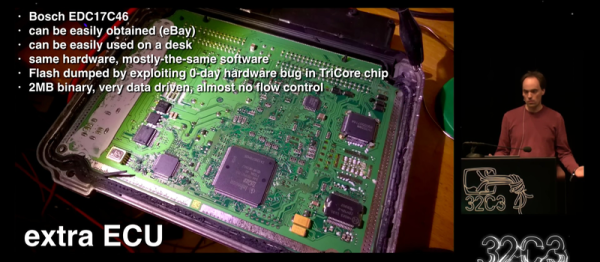

And so we come to an oft-forgotten aspect of computer security: the BIOS, UEFI, Intel’s Management Engine, VT-d, Boot Guard, and the mess of overly complex firmware found in a modern x86 system. This is what starts the chain of trust for the entire computer, and if a computer’s firmware is compromised it is safe to assume the entire computer is compromised. Firmware is also devilishly hard to secure: attacks against write protecting a tiny Flash chip have been demonstrated. A Trusted Platform Module could compare the contents of a firmware, and unlock it if it is found to be secure. This has also been shown to be vulnerable to attack. Another method of securing a computer’s firmware is the Core Root of Trust for Measurement, which compares firmware to an immutable ROM-like memory. The specification for the CRTM doesn’t say where this memory is, though, and until recently it has been implemented in a tiny Flash chip soldered to the motherboard. We’re right back to where we started, then, with an attacker simply changing out the CRTM chip along with the chip containing the firmware.

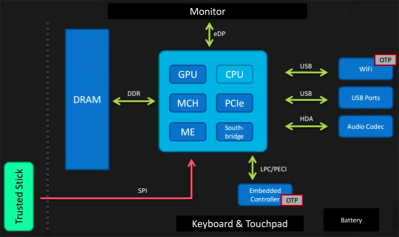

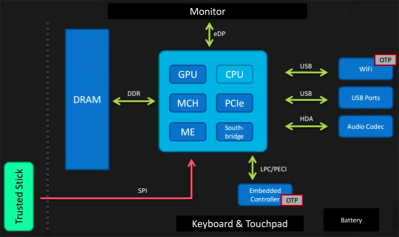

But Intel has an answer to everything, and to the house of cards for firmware security, Intel introduced their Management Engine. This is a small microcontroller running on every Intel CPU all the time that has access to RAM, WiFi, and everything else in a computer. It is security through obscurity, though. Although the ME can elevate privileges of components in the computer, nobody knows how it works. No one has the source code for the operating system running on the Intel ME, and the ME is an ideal target for a rootkit.

Is there hope for a truly secure laptop? According to [Joanna], there is hope in simply not trusting the BIOS and other firmware. Trust therefore comes from a ‘trusted stick’ – a small memory stick that contains a Flash chip that verifies the firmware of a computer independently of the hardware in a computer.

Is there hope for a truly secure laptop? According to [Joanna], there is hope in simply not trusting the BIOS and other firmware. Trust therefore comes from a ‘trusted stick’ – a small memory stick that contains a Flash chip that verifies the firmware of a computer independently of the hardware in a computer.

This, with open source firmwares like coreboot are the beginnings of a computer that can be trusted. While the technology for a device like this could exist, it will be a while until something like this will be found in the wild. There’s still a lot of work to do, but at least one thing is certain: secure hardware doesn’t exist, but it can be built. Whether secure hardware comes to pass is another thing entirely.

You can watch [Joanna]’s talk on the 32C3 streaming site.