As the prospects for Germany during the Second World War began to look increasingly grim, the Nazi war machine largely pinned their hopes on a number of high-tech “superweapons” they had in development. Ranging from upgraded versions of their already devastatingly effective U-Boats to tanks large enough to rival small ships, the projects ran the gamut from practical to fanciful. After the fall of Berlin there was a mad scramble by the Allied forces to get into what was left of Germany’s secretive development facilities, with each country hoping to recover as much of this revolutionary technology for themselves as possible.

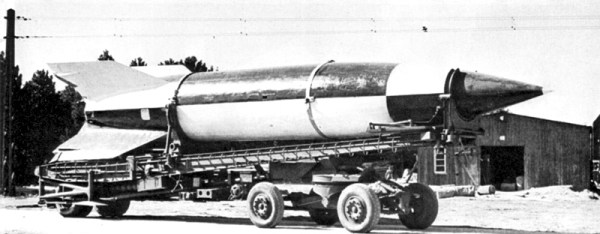

One of the most coveted prizes was the Aggregat 4 (A4) rocket. Better known to the Allies as the V-2, it was the world’s first liquid fueled guided ballistic missile and the first man-made object to reach space. Most of this technology, and a large number of the engineers who designed it, ended up in the hands of the United States as part of Operation Paperclip. This influx of practical rocketry experience helped kick start the US space program, and its influence could be seen all the way up to the Apollo program. The Soviet Union also captured V-2 hardware and production facilities, which subsequently influenced the design of their early rocket designs as well. In many ways, the V-2 rocket was the spark that started the Space Race between the two countries.

With the United States and Soviet Union taking the majority of V-2 hardware and personnel, little was left for the British. Accordingly their program, known as Operation Backfire, ended up being much smaller in scope. Rather than trying to bring V-2 hardware back to Britain, they decided to learn as much as they could about it in Germany from the men who used it in combat. This study of the rocket and the soldiers who operated it remains the most detailed account of how the weapon functioned, and provides a fascinating look at the incredible effort Germany was willing to expend for just one of their “superweapons”.

In addition to a five volume written report on the V-2 rocket, the British Army Kinematograph Service produced “The German A.4 Rocket”, a 40 minute film which shows how a V-2 was assembled, transported, and ultimately launched. Though they are operating under the direction of the British government, the German soldiers appear in the film wearing their own uniforms, which gives the documentary a surreal feeling. It could easily be mistaken for actual wartime footage, but these rockets weren’t aimed at London. They were being fired to serve as a historical record of the birth of modern rocketry.

Continue reading “Operation Backfire: Witness To The Rocket Age”