This half-inch square ultra-low power energy harvesting LiPo cell charger by [Kris Winer] uses a low voltage solar panel to top up a small lithium-polymer cell, which together can be used as the sole power source for projects. It’s handy enough that [Kris] uses them for his own projects and offers them for sale to fellow hackers. It’s also his entry into the Power Harvesting Challenge of the Hackaday Prize.

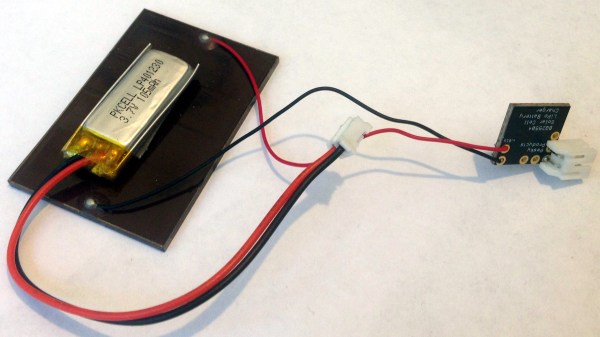

The board is essentially a breakout board for the Texas Instrument BQ25504, configured to charge and maintain a single lithium-polymer cell. The BQ25504 is an integrated part that takes care of most of the heavy lifting and has nifty features like battery health monitoring and undervoltage protection. [Kris] has been using the board along with a small 2.2 Volt solar panel and a 150 mAh LiPo cell to power another project of his: the SensorTile environmental data logger.

It’s a practical and useful way to test things; he says that an average of 6 hours of direct sunlight daily is just enough to keep the 1.8 mA SensorTile running indefinitely. These are small amounts of power, to be sure, but it’s free and self-sustaining which is just what a remote sensing unit needs.