Hackers love 3D printers. In fact, they might love them a little too much. We hope know we aren’t be the only ones who couldn’t turn down a good deal on an overseas printer (or two). But when you’re not pumping out plastic boats and other PLA dust collectors, what are you supposed to do with them?

Well if you’re like [Uri Shaked] you could hand them a pen and tell them to get writing. The holidays are coming up quick, and somebody’s gotta sign all these cards. In his detailed write-up, he shows how he was able to add a pen to his Creality CR-10 printer to turn it into a lean mean letter-writing machine without making any permanent changes to the printer.

Well if you’re like [Uri Shaked] you could hand them a pen and tell them to get writing. The holidays are coming up quick, and somebody’s gotta sign all these cards. In his detailed write-up, he shows how he was able to add a pen to his Creality CR-10 printer to turn it into a lean mean letter-writing machine without making any permanent changes to the printer.

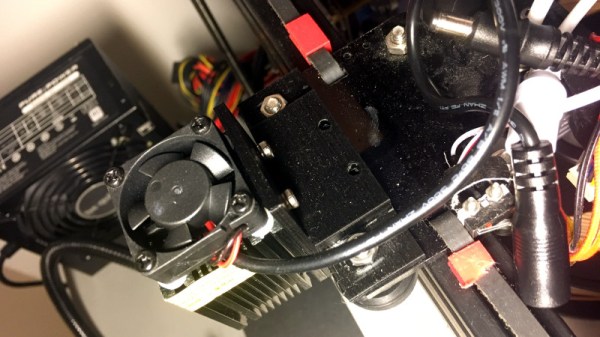

The physical aspect of this hack is about as simple as they come: just come up with some way to hold the pen a bit below the printer’s hotend. The positioning here is a bit critical, as you don’t want to crash the nozzle into the bed while writing out a missive. [Uri] got fancy and designed a little bracket that clamps onto the CR-10 and even has a M3 screw to hold the pen in place, but you could get away with zip ties if you just want to experiment a bit.

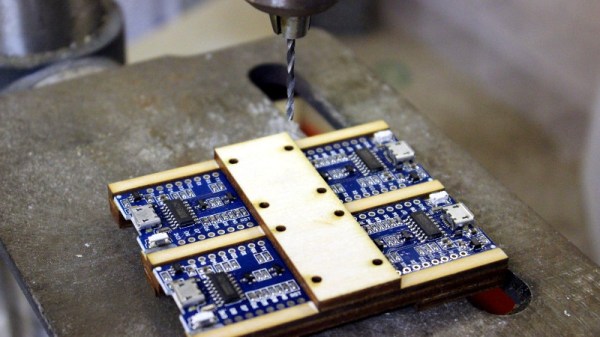

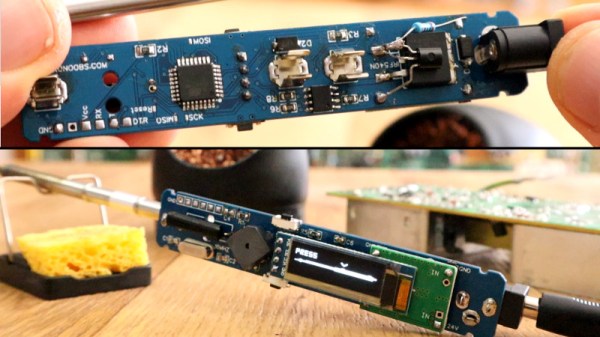

[Uri] goes into much greater detail on the software side of things, which is good, as it does take a bit of Inkscape trickery to get the printer to perform the specific dance moves required. He goes through step by step (with screen shots) explaining how to set up Orientation Points and configure the tool parameters for optimal performance. Even if you aren’t looking to put a 3D printer to work autographing your 8x10s before the next hackerspace meet, this is an excellent guide on producing GCode with Inkscape which can be helpful for tasks such as making PCBs.

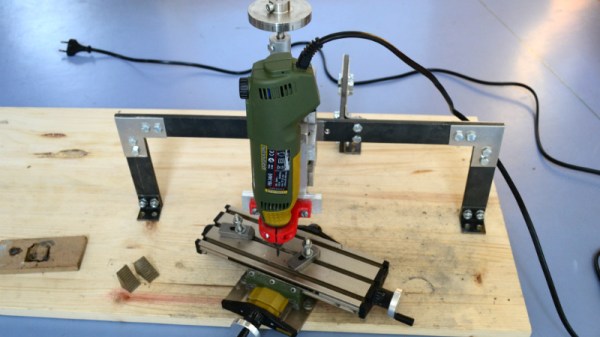

The general process here is very similar to adding a laser module to your 3D printer, but with considerably lower risk of your eyeballs doing their best Death Star impression.