We’ve all been there: faced with a tedious job that could be knocked out manually with a modest investment of time, we choose instead to overcomplicate the task and build something to do it for us. Such was the impetus behind this automated wire cutter, but in this case the ends justify the means.

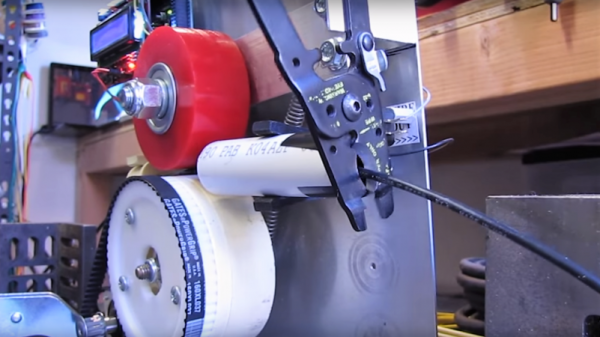

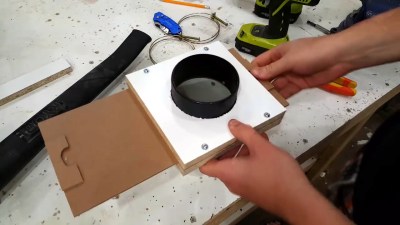

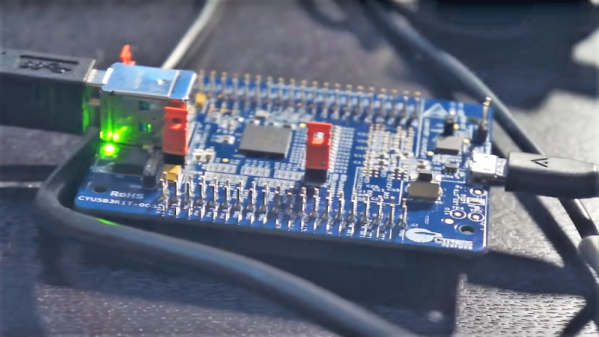

That [Edward Carlson] managed to stretch a twenty-minute session with wire cutters and a tape measure into four days of building and tweaking this machine is pretty impressive. The build process was jump-started by modifying an off-the-shelf wire measuring machine, of the kind one finds in the electrical aisle of The Big Orange Store. Stripped of the original mechanical totalizer and with a stepper added to drive the friction wheels, the machine can now measure cable by counting steps. A high-torque servo drives a stout pair of cable shears through a nifty linkage, or the machine can just measure the length of cable without cutting. [Edward]’s solution in search of a problem ends up bringing extra value, so maybe the time spent was worth it after all.

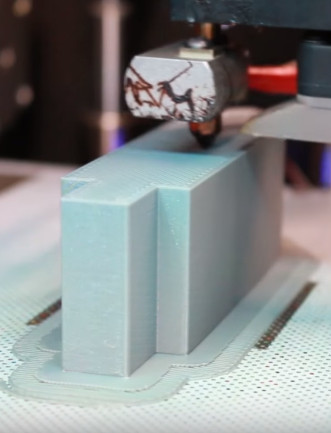

If the overall design looks familiar, you may be thinking of a similar of another cable-cutting bot we featured a while back. That one used a filament extruder and was for lighter gauge wires than this machine. Continue reading “Cable Cutting Machine Makes Fast Work Of A Tedious Job”