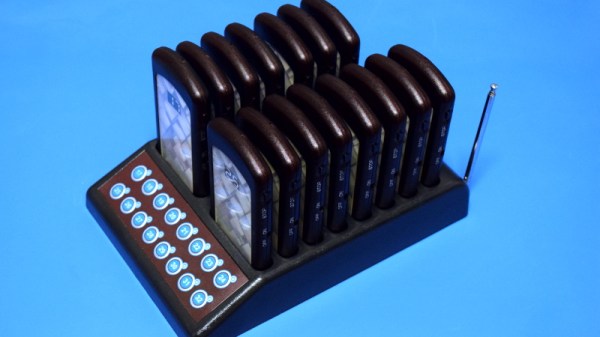

Amazon Dash buttons were the ultimate single purpose networked device; it really can’t get much simpler than a push button that sends a single message to a fixed endpoint. It was an experiment in ultimate convenience, an entry point to a connected home, and a target for critics of consumerism excess and technological overkill.

But soon they’ll be little more than a footnote in the history of online shopping, as CNet reports Amazon will take the order system offline at the end of the month. With the loss of their original intended usage, there’s nothing to stop us from hacking any Dash buttons we can get our hands on.

Of course, this decision should come as little surprise. Amazon’s in-home retail point of sale has graduated from these very limited $5 buttons to Alexa-powered voice controlled devices. Many people also carry a cell phone at all times capable of submitting Amazon orders. While there are many good reasons to be skeptical of internet connected appliances, they’re undeniably finding a niche in the market and some have integrated their own version of a Dash button to re-order household supplies.

But are hackers still interested in hacking Dash buttons? Over the lifespan of Amazon Dash buttons, our project landscape has shifted as well. We’re certainly still interested in the guts an Echo Dot. But if we wanted to build a simple networked button, we can use devices like an ESP8266 which are almost as cheap and far easier to use. Using something intended for integration means we don’t have headaches like determining which generation hardware we have.

Despite those barriers, we’ve had many Dash button hacks on these pages. A to-do list updater was the most recent and we doubt it will be the last, especially as Amazon’s deactivation should mean a whole new flood of these buttons will become available for hacking.

[via Ars Technica]