Scope creep is a real pain in the real world, but for projects of passion it can have some interesting consequences. [rctestflight] was playing around with 3D printed rover gearboxes, which morphed into a 3D printed tank build.

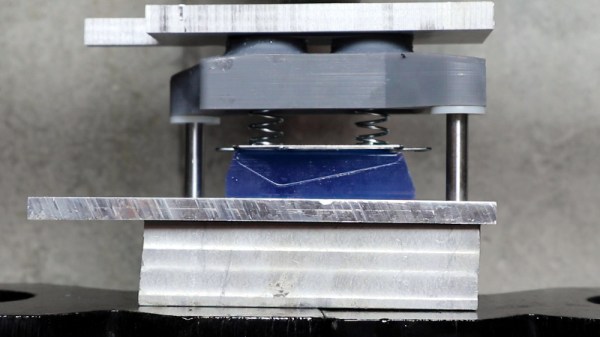

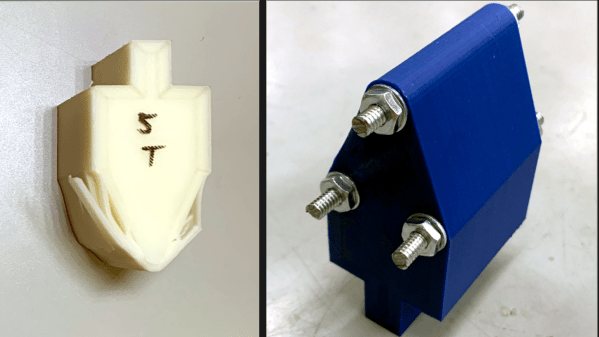

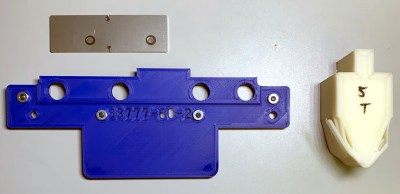

[rctestflight]’s previous autonomous rover project had problems with the cheap geared motors, and he started experimenting with his own gearbox designs to use with lower RPM / Kv brushless drone motors. The tank came about because he wanted a simple vehicle to test his design. “Simple” went out the window pretty quickly and the final product was completely 3D printed except for the fasteners, axles, bearings, and electronics.

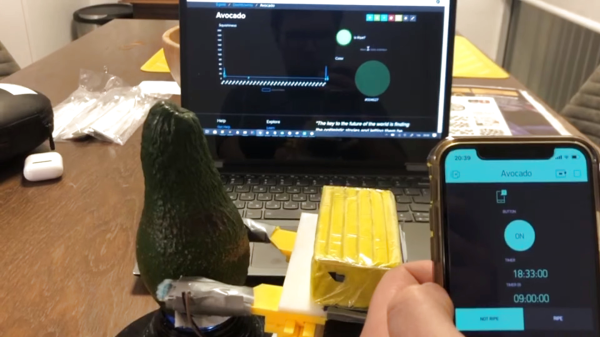

The tracks and gears are noisy, but it works quite well. On outdoor tests [rctestflight] did find that the tracks were prone to hooking on vines and branches, which in one case caused it to throw a track after the aluminium shaft bent. An Ardurover navigation system was added and with a 32 Ah battery was able to run autonomously for an entire day and there was surprisingly little wear on 3D printed gearbox and tracks afterward. All the STL files are up on Thingiverse, but [rctestflight] recommends waiting for an upcoming update because he discovered flaws in the design after filming the video after the break.

For a slightly more complex and expensive rover, check out our coverage of Perseverance, NASA’s MARS 2020 Rover. Continue reading “Autonomous 3D Rover With Tank Tracks Rules The Fields. Almost”