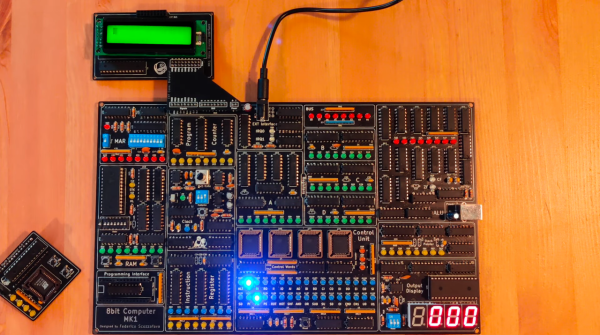

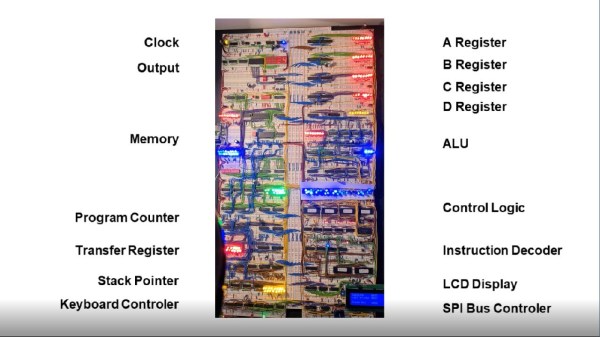

Some projects are a rite of passage within their respected fields. For computer science, building one’s own computer from scratch is certainly among those projects. Of course, we’re not talking about buying components online and snapping together a modern x86 machine. We mean building something closer to a fully-programmable 8-bit computer from the ground up, like this one from [Federico] based on 74LS logic chips.

The computer was designed and built from scratch which is impressive enough, but [Federico] completed this project in about a month as well. It can be programmed manually through DIP switches or via a USB connection to another computer, and also includes an adjustable clock which can perform steps anywhere from 1 Hz to 32 kHz. Complete with a 1024 byte memory, a capable ALU, four seven-segment LEDs and (in the second version of the computer) a 2×16 LCD disply, this 8-bit computer has it all.

Not only is this a capable machine designed by someone who clearly knows his way around a logic chip, but [Federico] has also made the code and schematics available on his GitHub page. It’s worth a read even without building your own, but if you want to go that route without printing an enormous PCB you can always follow the breadboard route.

Thanks to [killergeek] for the tip!