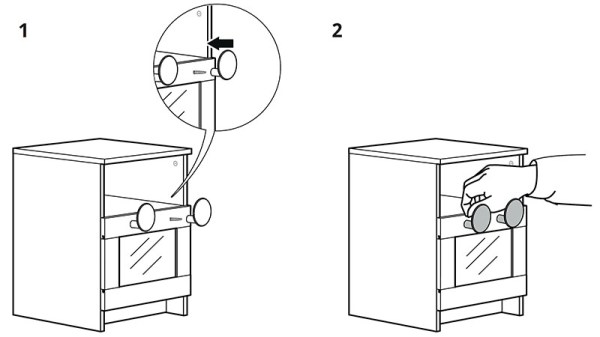

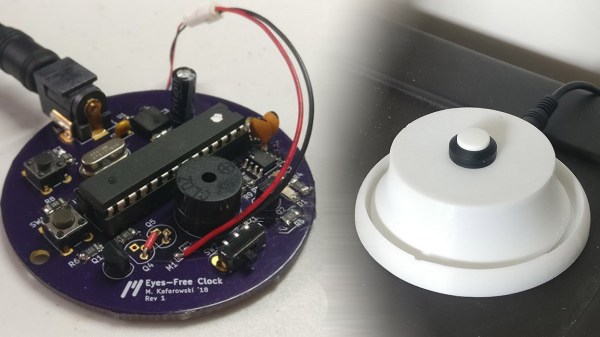

Picture this: You’re in your bed in the middle of the night, and you want to know what time it is. Bedside alarm clocks are a thing of the past and now you rely on your smartphone to tell the time. Only, if you turned the screen on, you’d find that looking at it in the dark is tantamount to staring at the sun without eye protection. [Michael] pictured the same thing and his solution for this scenario is a clever haptic-feedback clock.

The idea behind it is simple, a clock from which you can tell the time without having to use your eyes. This one gives you two options for that, the first one being a series of haptic pulses that let you tell the time simply by touching the device. The second, audibly telling the time with voice samples stored in a flash chip, was added in the second revision as [Michael] continues to refine his design. In addition to helping us assess the time in the dark, it’s also worth noting that this could be useful for those with visual impairments as well.

Until we can see the final product, you can help him out looking over the designs and sending pull requests over at the project’s GitHub page, or just watch his progress in the Hackaday.io page. We’ve seen some interesting ways to tell the time before, from a game of Tetris to a clock housed inside the shell of an old-school camera flash, but we’ve never seen one that uses haptic feedback before. We hope for the sake of our eyes that it catches on!

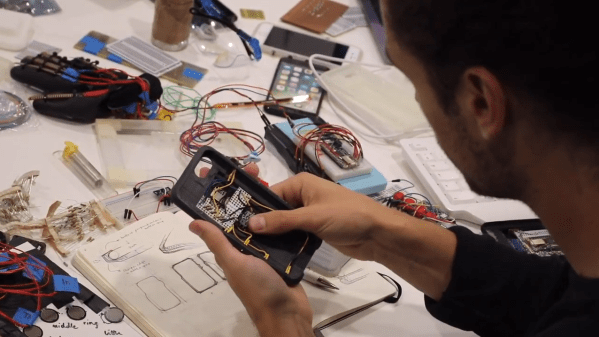

Smartphones and other modern computing devices are wonderful things, but for those with disabilities interacting with them isn’t always easy. In trying to improve accessibility, [Dougie Mann] created

Smartphones and other modern computing devices are wonderful things, but for those with disabilities interacting with them isn’t always easy. In trying to improve accessibility, [Dougie Mann] created