With a GPS on every smartphone, one would be forgiven for forgetting that handheld GPS units still exist. Seeking to keep accurate data on a few upcoming trips, [_Traveler] took on a custom-build that resulted in this GPS data logger.

![]() Keeping tabs on [_Traveler] is a Ublox M8N GPS which is on full-time, logging data every 30 seconds, for up to 2.5 days. All data is saved to an SD card, with an ESP32 to act as a brain and make downloading the info more accessible via WiFi . While tracking the obvious — like position, speed, and time — this data logger also displays temperature, elevation, dawn and dusk, on an ePaper screen which is a great choice for conserving battery.

Keeping tabs on [_Traveler] is a Ublox M8N GPS which is on full-time, logging data every 30 seconds, for up to 2.5 days. All data is saved to an SD card, with an ESP32 to act as a brain and make downloading the info more accessible via WiFi . While tracking the obvious — like position, speed, and time — this data logger also displays temperature, elevation, dawn and dusk, on an ePaper screen which is a great choice for conserving battery.

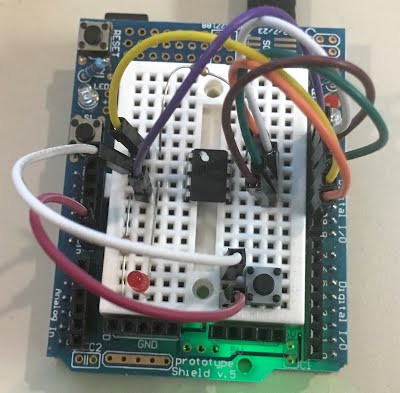

The prototyping process is neat on this one. The first complete build used point-to-point soldering on a protoboard to link several breakout modules together. After that, a PCB design embraces the same modules, with a footprint for the ESP’s castellated edges and header footprints for USB charing board, SD card board, ePaper, etc. All of this finds a hope in a 3D printed enclosure. After a fair chunk of time coding in the Arduino IDE the logger is ready for [_Traveler]’s next excursion!

As far as power consumption in the field, [_Traveler] says the GPS takes a few moments to get a proper location — with the ESP chewing through battery life all the while — and plans to tinker with it in shorter order.

Not all GPS trackers are created equal: sometimes all you need is a stripped-down tracker for your jog, or to know exactly where every pothole is along your route.

[Via /r/electronics]