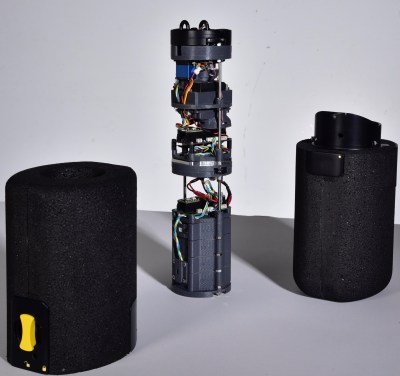

[Neumi] over on Hackaday.IO wanted a simple-to-use way to drive stepper motors, which could be quickly deployed in a wide variety of applications yet to be determined. The solution is named Ethersweep, and is a small PCB stack that sits on the rear of the common NEMA17-format stepper motor. The only physical connectivity, beside the motor, are ethernet and a power supply via the user friendly XT30 connector. The system can be closed loop, with both an end-stop input as well as an on-board AMS AS5600 magnetic rotary encoder (which senses the rotating magnetic field on the rear side of the motor assembly – clever!) giving the necessary feedback. Leveraging the Trinamic TMC2208 stepper motor driver gives Ethersweep silky smooth and quiet motor control, which could be very important for some applications. A rear-facing OLED display shows some useful debug information as well as the all important IP address that was assigned to the unit.

Control is performed with the ubiquitous ATMega328 microcontroller, with the Arduino software stack deployed, making uploading firmware a breeze. To that end, a USB port is also provided, hooked up to the uC with the cheap CP2102 USB bridge chip as per most Arduino-like designs. The thing that makes this build a little unusual is the ethernet port. The hardware side of things is taken care of with the Wiznet W5500 ethernet chip, which implements the MAC and PHY in a single device, needing only a few passives and a magjack to operate. The chip also handles the whole TCP/IP stack internally, so only needs an external SPI interface to talk to the host device.

making uploading firmware a breeze. To that end, a USB port is also provided, hooked up to the uC with the cheap CP2102 USB bridge chip as per most Arduino-like designs. The thing that makes this build a little unusual is the ethernet port. The hardware side of things is taken care of with the Wiznet W5500 ethernet chip, which implements the MAC and PHY in a single device, needing only a few passives and a magjack to operate. The chip also handles the whole TCP/IP stack internally, so only needs an external SPI interface to talk to the host device.

Continue reading “Ethersweep: An Easy-To-Deploy Ethernet Connected Stepper Controller”