We’ll be honest right up front: there’s nothing new in [David Cambridge]’s brushless motor and controller build. If you’re looking for earth-shattering innovation, you’d best look elsewhere. But if you enjoy an aimless use of just about every technique and material in the hacker’s toolkit employed with extreme craftsmanship, then this might be for you. And Nixies — he’s got Nixies in there too.

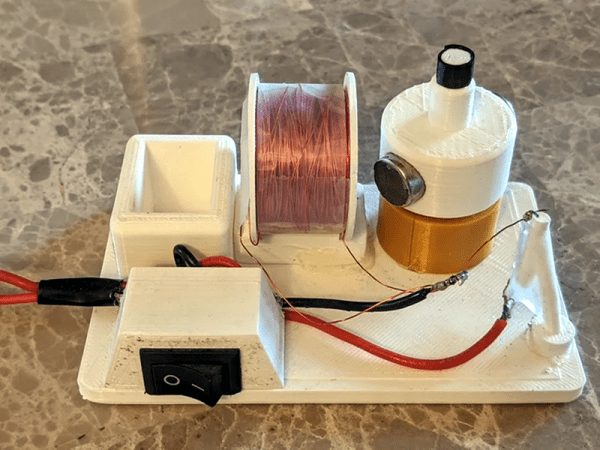

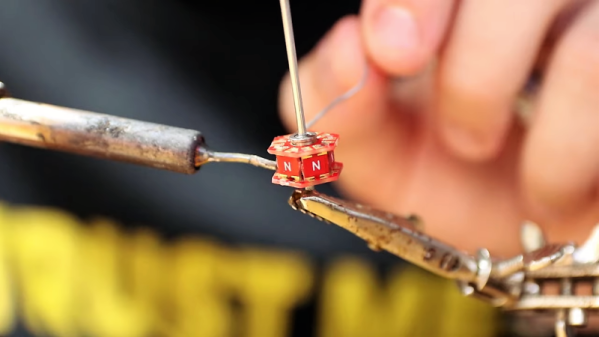

[David]’s build started out as a personal exploration of brushless motors and how they work. Some 3D-printed parts, a single coil of wire, and a magnetic reed switch resulted in a simple pulse motor that performed surprisingly well. This morphed into a six-coil motor with Hall-effect sensors and a homebrew controller. This is where [David] pulled out all the stops on tools — a lathe, a plasma cutter, a welder, a milling machine, and a nice selection of woodworking tools went into making parts for the final motor as well as an enclosure for the project. And because he hadn’t checked off quite all the boxes yet, [David] decided to use the 3D-printed frame as a pattern for casting one from aluminum.

The finished motor, with a redesigned rotor to deal better with eddy currents, joined the wood and metal enclosure along with a Nixie tube tachometer and etched brass control plates. It’s a great look for a project that’s clearly a labor of self-edification and skill-building, and we love it. We’ve seen other BLDC demonstrators before, but few that look as good as this one does.

Continue reading “Steampunk Brushless Motor Demo Pushes All The Maker Buttons”