In the last few months, most of the world’s population has shied away from touching as many public things as possible. Unfortunately, anyone with low vision who relies on Braille signs, relief maps, and audio jacks doesn’t have this luxury — at least not yet.

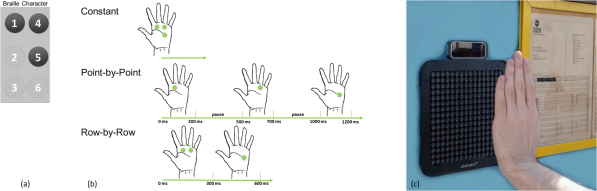

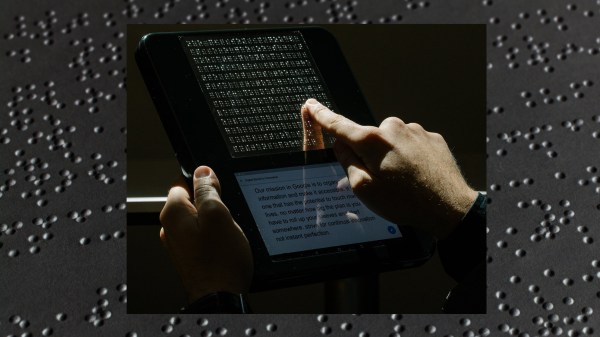

A group of researchers at Bayreuth University in Germany are most of the way to solving this problem. They’re developing HaptiRead, a mid-air haptic feedback system that can be used as a touchless, refreshable display for Braille or 3D shapes. HaptiRead is based on a Stratos Explore development kit that has a field of 256 ultrasonic transducers. When a person approaches the display, a Leap motion sensor can detect their hand from up to 2.5 feet away and start providing information via sound waves. Each focus point is modulated with a different frequency to help differentiate between them.

HaptiRead can display information three ways: constant, which imitates static Braille displays, point by point, and row by row. The researchers claim up to 94% accuracy in trials, with the point by point method in the lead. The system is still a work in progress, as it can only do four cells’ worth of dot combination and needs to do six before it’s ready. Check out the brief explainer video after the break, or read the group’s paper [PDF download].

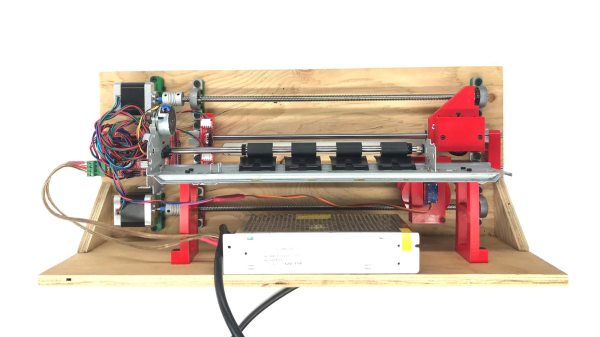

Want to play with refreshable Braille systems? This open-source display uses Flexinol wire to actuate the dots.

Continue reading “Hands-Free Haptic Braille Display Is Making Waves”