Tesla Coils are a favourite here at Hackaday – just try searching through the archives, and see the number of results you get for all types of cool projects. [mircemk] adds to this list with his Extremely simple Tesla Coil with only 3 Components. But Be Warned — most Tesla coil designs can be dangerous and ought to be handled with care — and this one particularly so. It connects directly to the 220 V utility supply. If you touch any exposed, conductive part on the primary side, “Not only will it kill You, it will hurt the whole time you’re dying”. Making sure there is an ELCB in the supply line will ensure such an eventuality does not happen.

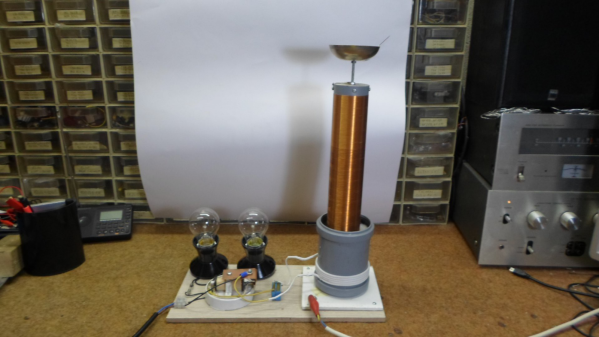

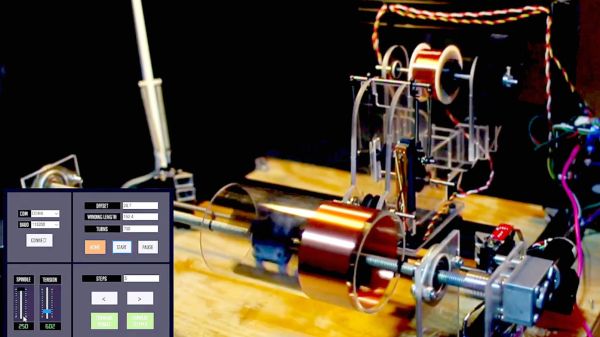

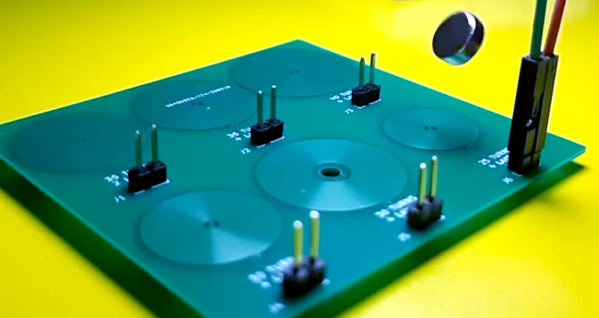

No prizes for guessing that the circuit is straight forward. It can be built with parts lying around the typical hacker den. Since the coil runs directly off 220 V, [mircemk] uses a pair of fluorescent lamp ballasts (chokes) to limit current flow. And if ballasts are hard to come by, you can use incandescent filament lamps instead. The function of the “spark gap” is done by either a modified door bell or a 220 V relay. This repeatedly charges the capacitor and connects it across the primary coil, setting up the resonant current flow between them. The rest of the parts are what you would expect to see in any Tesla coil. A high voltage rating capacitor and a few turns of heavy gauge copper wire form the primary LC oscillator tank circuit, while the secondary is about 1000 turns of thinner copper wire. Depending on the exact gauge of wires used, number of turns and the diameter of the coils, you may need to experiment with the value of the capacitor to obtain the most electrifying output.

If you have to look for one advantage of such a circuit, it’s that there is not much that can fail in terms of components, other than the doorbell / relay, making it a very robust, long lasting solution. If you’d rather build something less dangerous, do check out the huge collection of Tesla Coil projects that we have featured over the years.

Continue reading “Extremely Simple Tesla Coil With Only 3 Components”