On Tech Twitter, some people are known for Their Thing – for example, [A13 (@sad_electronics)], (when they’re not busy designing electronics), searches the net to find outstanding parts to marvel at. A good portion of the parts that they find are outstanding for all the wrong reasons. Today, that’s a through-hole two-pin USB Type-C socket. Observing the cheap tech we get from China (or the UK!), you might conclude that two 5.1K pulldown resistors are very hard to add to a product – this socket makes it literally impossible.

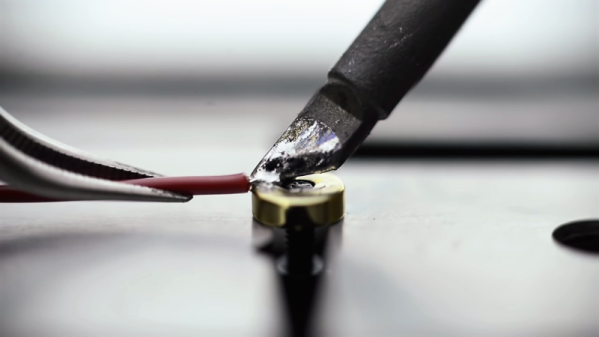

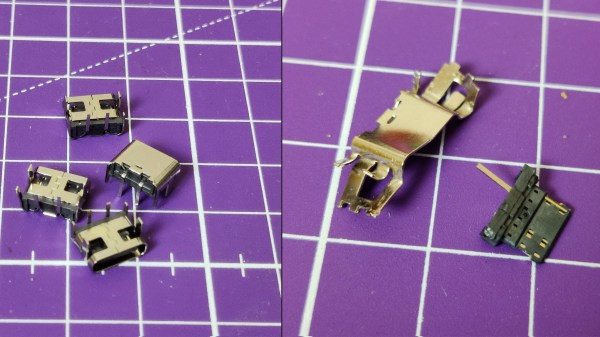

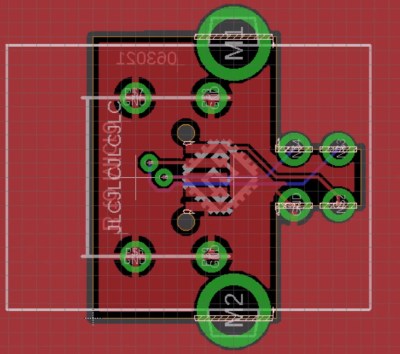

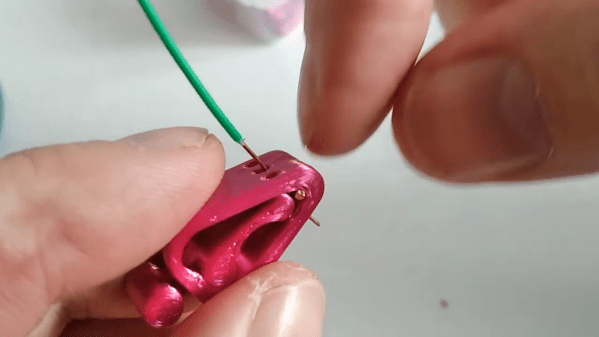

We’ve seen two-pin THT MicroUSB sockets before, sometimes used for hobbyist kits. This one, however, goes against the main requirement of Type-C connectors – sink (Type-C-powered) devices having pulldowns on CC pins, and source devices (PSUs and host ports) having pull up resistors to VBUS. As disassembly shows, this connector has neither of these nor the capability for you to add anything, as the CC pins are physically not present. If you use this port to make a USB-C-powered device, a Type-C-compliant PSU will not give it power. If you try to make a Type-C PSU with it, a compliant device shall (rightfully!) refuse to charge from it. The only thing this port is good for is when a device using it is bundled with a USB-A to USB-C cable – actively setting back whatever progress Type-C connectors managed to make.

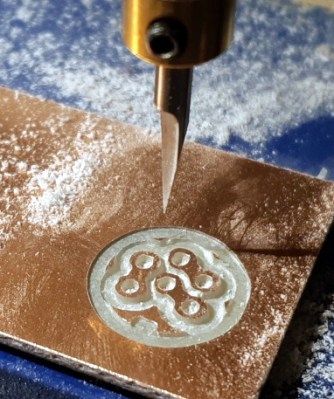

As much as USB Type-C basics are straightforward, manufacturers get it wrong on the regular – back in 2016, a wrong cable could kill your $1.5k MacBook. Nowadays, we might only need to mod a device with a pair of 5.1K resistors every now and then. We can only hope that the new EU laws will force devices to get it right and stop ruining the convenience for everyone, so we can finally enjoy what was promised to us. Hackers have been making more and more devices with USB-C ports, and even retrofitting iPhones here and there. If you wanted to get into mischief territory and abuse the extended capabilities of new tech, you could even make a device that enumerates in different ways if you flip the cable, or make a “BGA on an FPC” dongle that is fully hidden inside a Type-C cable end!

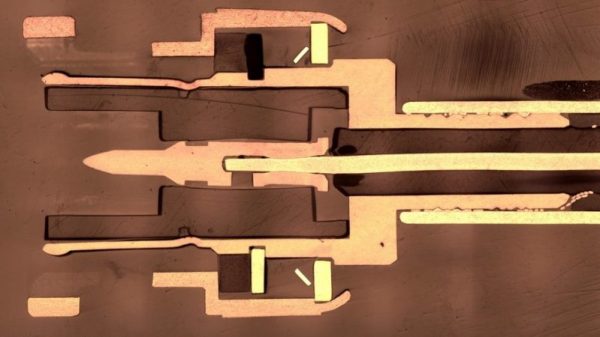

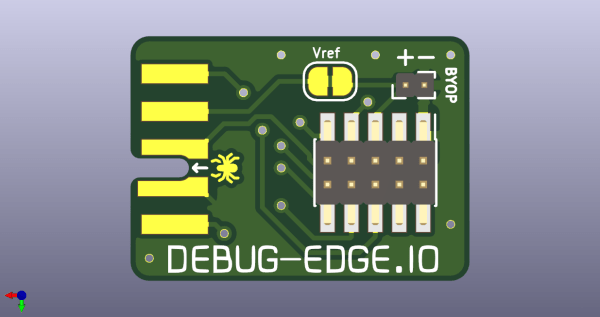

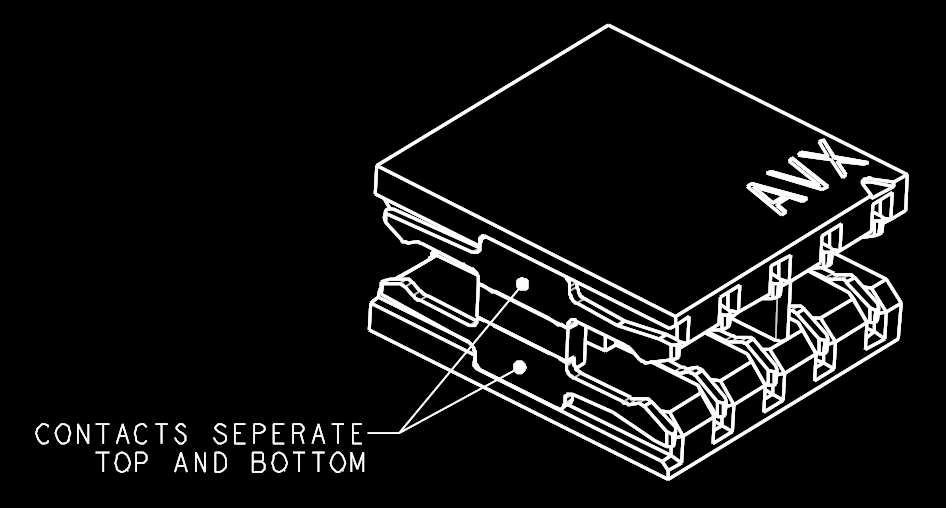

The name “Debug Edge” says it all. It’s a debug, edge connector. A connector for the edge of a PCBA to break out debug signals. Card edge connectors are nothing new but they typically either slot one PCBA perpendicularly into another (as in a PCI card) or hold them in parallel (as in a mini PCIe card or an m.2 SSD). The DebugEdge connector is more like a PCBA butt splice.

The name “Debug Edge” says it all. It’s a debug, edge connector. A connector for the edge of a PCBA to break out debug signals. Card edge connectors are nothing new but they typically either slot one PCBA perpendicularly into another (as in a PCI card) or hold them in parallel (as in a mini PCIe card or an m.2 SSD). The DebugEdge connector is more like a PCBA butt splice.