[Robert Murray-Smith] presents for us an interesting electronic device from years gone by, before the advent of Silicon semiconductors, the humble metal oxide rectifier. After the electronic dust had settled following the brutal AC/DC current wars of the late 19th century — involving Edison, Tesla and Westinghouse to name a few of the ringleaders — AC was the eventual winner. But there was a problem. It’s straightforward to step down the high voltage AC from the distribution network to a more manageable level with a transformer, and feed that straight into devices which can consume alternating current such as light bulbs and electrical heaters. But other devices really want DC, and to get that, you need a rectifier.

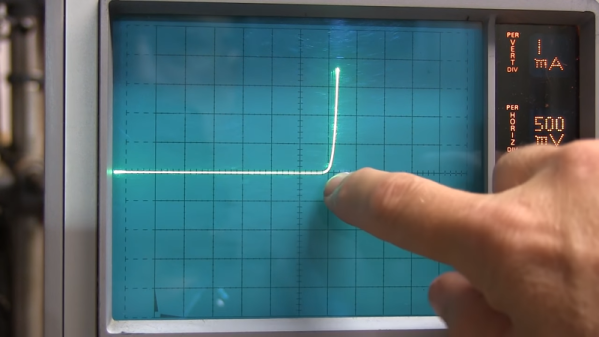

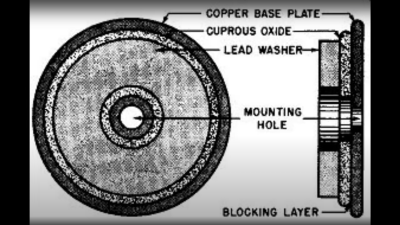

It turns out, that even in those early days, we had semiconductor devices which could perform this operation, based not upon silicon or germanium, but copper. Copper (I) Oxide is a naturally occurring P-type semiconductor, which can be easily constructed by heating a copper sheet in a flame, and scraping off the outer layer of Copper (II) Oxide leaving the active layer below. Simply making contact to a piece of steel is sufficient to complete the device.

based not upon silicon or germanium, but copper. Copper (I) Oxide is a naturally occurring P-type semiconductor, which can be easily constructed by heating a copper sheet in a flame, and scraping off the outer layer of Copper (II) Oxide leaving the active layer below. Simply making contact to a piece of steel is sufficient to complete the device.

Obviously a practical rectifier is a bit harder to make, with a degree of control required, but you get the idea. A CuO metal rectifier can rectify as well as operate as a thermopile, and even as a solar cell, it’s just been forgotten about once we got all excited about silicon.

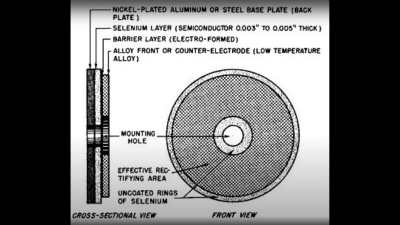

Other similar metallic rectifiers also saw some action, such  as the Selenium rectifier, based on the properties of a Cadmium Selenide – Selenium interface, which forms an NP junction, albeit one that can’t handle as much power as good old copper. One final device, which was a bit of an improvement upon the original CuO rectifiers, was based upon a stack of Copper Sulphide/Magnesium metal plates, but they came along too late. Once we discovered the wonders of germanium and silicon, it was consigned to the history books before it really saw wide adoption.

as the Selenium rectifier, based on the properties of a Cadmium Selenide – Selenium interface, which forms an NP junction, albeit one that can’t handle as much power as good old copper. One final device, which was a bit of an improvement upon the original CuO rectifiers, was based upon a stack of Copper Sulphide/Magnesium metal plates, but they came along too late. Once we discovered the wonders of germanium and silicon, it was consigned to the history books before it really saw wide adoption.

We’ve covered CuO rectifiers before, but the Copper Sulphide/Magnesium rectifier is new to us. And if you’re interested in yet more ways to steer electrons in one direction, checkout our coverage of the history of the diode.