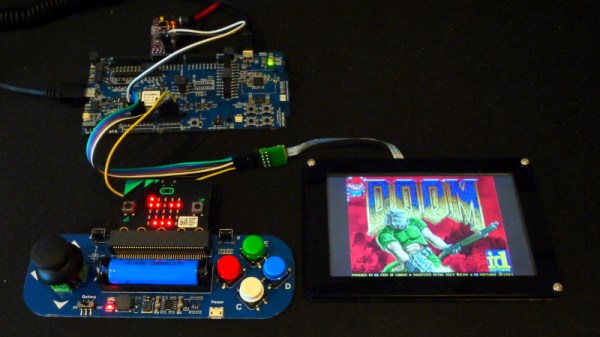

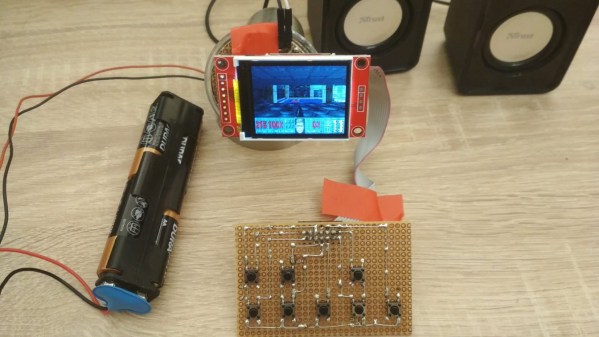

Getting DOOM to run on hardware it was never intended to run on is a tradition as old as time. Old cell phones, embedded systems, and ancient televisions have all been converted to play this classic first-person shooter. This style of playing games on old hardware might be passé now as the new trend seems to be the ability to play this game on more ethereal platforms instead. This project brings DOOM to Twitter.

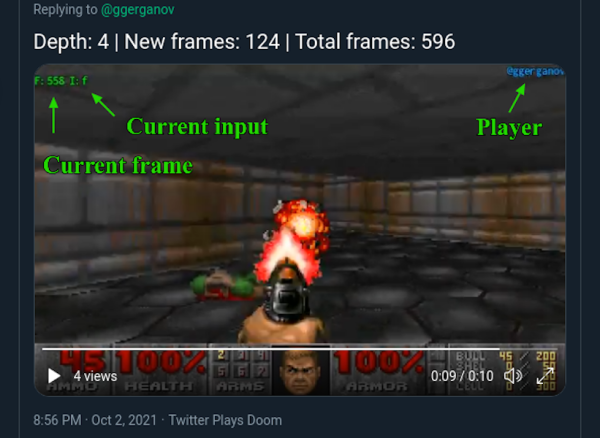

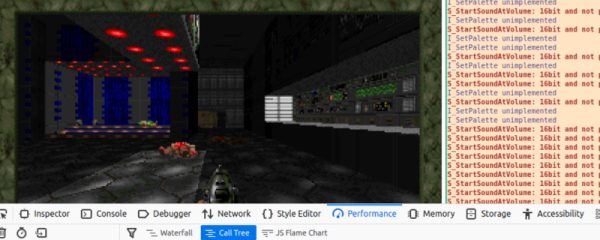

The gameplay is a little nontraditional as well. To play the game, a tweet needs to be sent with specific instructions for the bot. The bot then plays the game according to its instructions and then tweets a video. By responding to this tweet with more instructions, the player can continue the game tweet-by-tweet. While slightly cumbersome, it does have the advantage of allowing a player to resume any game simply by responding to the tweet where they would like to start. Behind the scenes of the DOOM-playing Twitter bot is interesting as well and the code is available on the project’s GitHub page.

While we’ve seen plenty of DOOM instances on all kinds of hardware, it’s safe to say we’ve never really seen a gameplay experience quite like this one. It may stay as a curiosity, but DOOM porters are always looking for something else to run this classic game so it may eventually branch out or develop into something more user-friendly like this cloud-based Atari 2600.