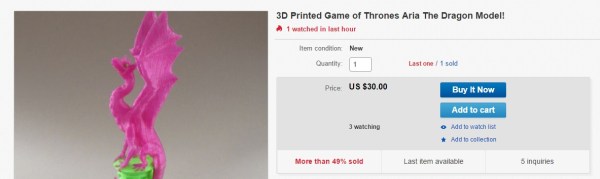

[Louise] tried out her new E3D Cyclops dual extrusion system by printing a superb model dragon. The piece was sculpted in Blender, stands 13cm tall and can be made without supports. It’s an impressive piece of artwork that reflects the maker’s skill, dedication and hard work. She shared her creation on the popular Thingiverse website which allows others to download the file for use on their own 3D printer. You can imagine her surprise when she stumbled upon her work being sold on eBay.

It turns out that the owner of the eBay store is not just selling [Louise]’s work, he’s selling thousands of other models taken from the Thingiverse site. This sketchy and highly unethical business model has not gone unnoticed, and several people have launched complaints to both Thingiverse and eBay. Now, there are lots of things to talk about here, but the 800 pound high voltage transformer in the room is the legality of the whole thing. What he’s doing might be unethical, but is it illegal?

When [Louise] politely asked the eBay store owner to remove her work, he responded with:

“When you uploaded your items onto Thingiverse for mass distribution, you lost all rights to them whatsoever. They entered what is known in the legal world as “public domain”. The single exception to public domain rules are original works of art. No court in the USA has yet ruled a CAD model an original work or art.”

Most of the uploaded CAD models on Thingiverse are done under the Creative Commons license, which is pretty clear in its assertion that anyone can profit from the work. This would seem to put the eBay store owner in the clear for selling the work, but it should be noted that he’s not properly attributing the work to the original creator. There are other derivatives of the license, some of which prohibit commercial use of the work. In these cases, the eBay store owner would seem to be involved in an obvious violation of the license.

There are also questions stirring with his use of images. He’s not taking the CAD model and making his own prints for images. He lifting the images of the prints from the Thingiverse site along with the CAD files. It’s a literal copy/paste business model.

With that said, the eBay store owner makes a fairly solid argument in the comments section of the post that broke the news. Search for the poster named “JPL” and the giant brick of text to read it. He argues that the Thingiverse non-commercial license is just lip service and has no legal authority. One example of this is how they often provide links to companies that will print a CAD design on the same page of a design that’s marked as non-commercial. He sums up one of many good points with the quote below:

“While we could list several other ways Thingiverse makes (money), any creator should get the picture by now-Thingiverse exists to make Stratasys (money) off of creators’ designs in direct violation of its very own “non-commercial” license. If a creator is OK with a billion-dollar Israeli company monetizing his/her designs, but hates on a Philly startup trying to make ends-meet, then they have a very strange position indeed.”

OK Hackaday readers, you have heard both sides of the issue. Here’s the question(s):

1. Is the eBay seller involved in illegal activity?

2. Can he change his approach to stay within the limits of the license? For instance, what if he credits the original maker on the sale page?

3. How would you feel if you found your CAD file for sale on his eBay store?