It might seem a little bit counterintuitive, but one of the more carbon-neutral ways of heating one’s home is by burning wood. Since the carbon for the trees came out of the air a geologically insignificant amount of time ago, it’s in effect solar energy with extra steps. And with modern stoves and well-seasoned wood, air pollution is minimized as well. The only downside is needing to feed the fire frequently, which [Anders] solved by building a robot.

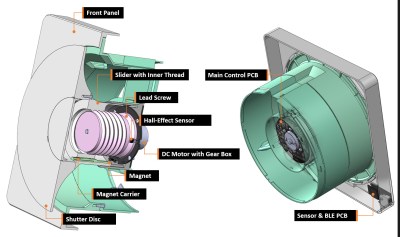

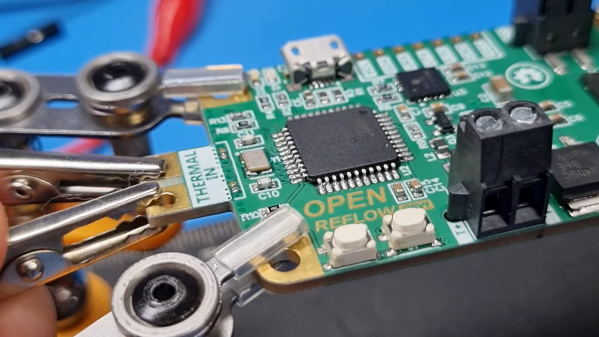

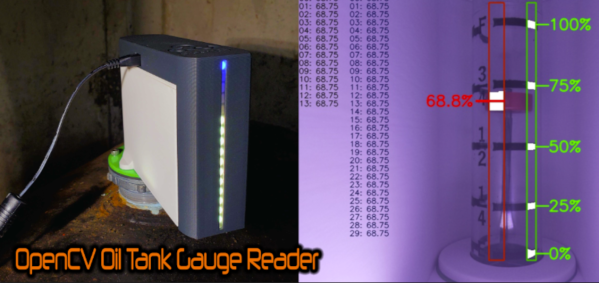

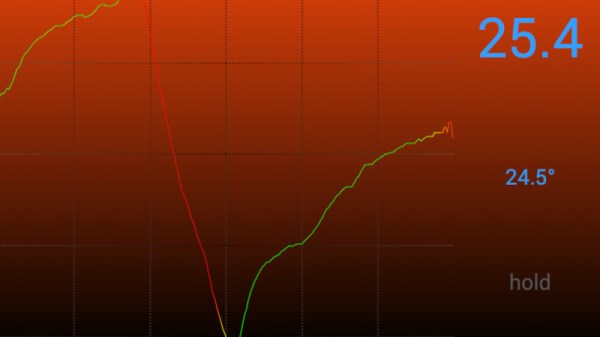

[Anders]’ system is centered around a boiler, a system which typically sits in a utility area like a basement and directs its heat to the home via another system, usually hot water. An Arduino Mega controls the system of old boat winches and various motors, with a grabber arm mounted at the end. The arm pinches each log from end to end, allowing it to grab the uneven logs one at a time. The robot also opens the boiler door and closes it again when the log is added, and then the system waits for the correct set of temperature conditions before grabbing another log and adding it. And everything can be monitored remotely with the help of an ESP32.

The robot is reportedly low-maintenance as well, thanks to its low speed and relatively low need for precision. The low speed also makes it fairly safe to work around, which was an important consideration because wood still needs to be added to a series of channels every so often to feed the robot, but this is much less often than one would have to feed logs into a boiler if doing this chore manually. It also improves on other automated wood-burning systems like pellet stoves, since you can skip the pellet-producing middleman step. It also eliminates the need to heat your home by burning fossil fuels, much like this semi-automated wood stove.