Last year, we saw quite a bit of media attention paid to blockchain startups. They raised money from the public, then most of them vanished without a trace (or product). Ethics and legality of their fundraising model aside, a few of the ideas they presented might be worth revisiting one day.

One idea in particular that I’ve struggled with is the synthesis of IoT and blockchain technology. Usually when presented with a product or technology, I can comprehend how and/or why someone would use it – in this case I understand neither, and it’s been nagging at me from some quiet but irrepressible corner of my mind.

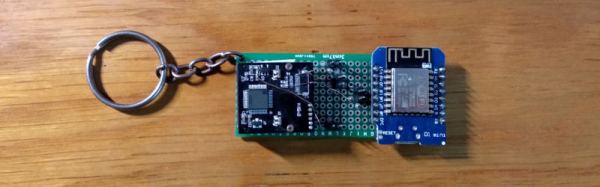

The typical IoT networks I’ve seen collect data using cheap and low-power devices, and transmit it to a central service without more effort spent on security than needed (and sometimes much less). On the other hand, blockchains tend to be an expensive way to store data, require a fair amount of local storage and processing power to fully interact with them, and generally involve the careful use of public-private key encryption.

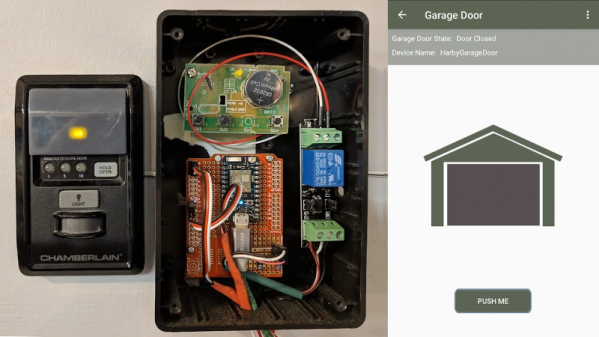

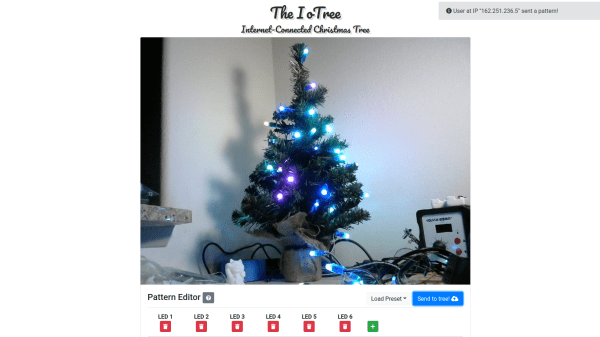

I can see some edge cases where it would be useful, for example securely setting the state of some large network of state machines – sort of like a more complex version of this system that controls a single LED via Ethereum smart contract.

What I believe isn’t important though, perhaps I just lack imagination – so lets build it anyway.

Continue reading “Yes, You Can Put IoT On The Blockchain Using Python And The ESP8266”