We like to think our readers are on the cutting edge. With the advent of CRISPR kits at home and DIY bio blooming in workshops across the world, we wanted to share a video which may be ahead of its time. [The Thought Emporium] has just shown us a way to store eukaryotic cells at room temperature. His technique is based on a paper published in Nature which he links to from the YouTube page, but you can see his video after the break.

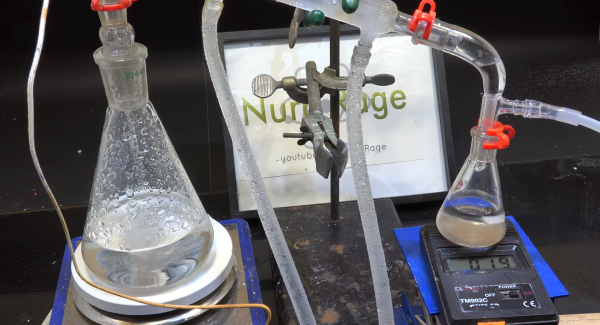

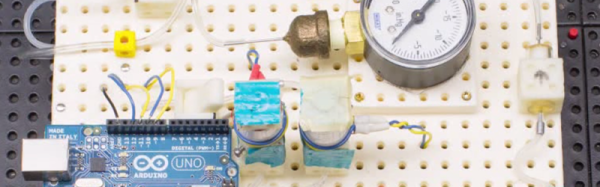

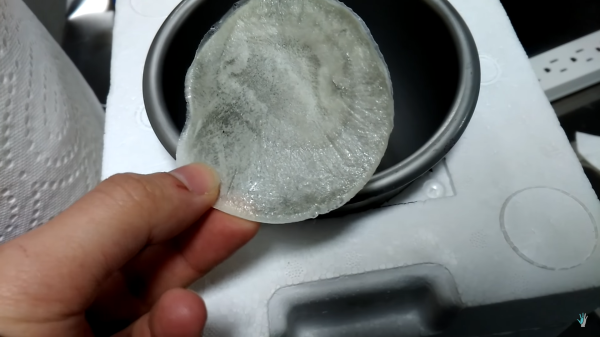

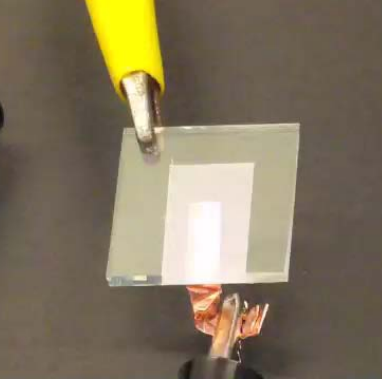

Eukaryotic cells, the kind we are made of, have been transported at low temperatures with techniques like active refrigeration, liquid nitrogen, and dry ice but those come with a host of problems like cost, convenience, and portability. Storing the cells with cryogel has been shown to reliably keep the cells stable for up to a week at a time and [The Thought Emporium] made some in his homemade freeze-dryer which he’s shown us before. The result looks like a potato chip, but is probably less nutrious than astronaut ice cream.

If cell transport doesn’t tickle your fancy, cryogel is fascinating by itself as a durable, lightweight insulator similar to Aerogel. You can make Aerogel at home too.

Continue reading “DIY Cryogel Sustains Live Cells”

Hackaday reader [gratian] tipped us off about the course available from

Hackaday reader [gratian] tipped us off about the course available from