[Fraens] has been re-making industrial machines in fantastic 3D-printable versions for a few years now, and we’ve loved watching his creations get progressively more intricate. But with this nearly completely 3D-printable needle loom, he’s pushing right up against the edge of the possible.

The needle loom is a lot like the flying shuttle loom that started the Industrial Revolution, except for making belts or ribbons. It’s certainly among the most complex 3D-printed machines that we’ve ever seen, and [Fraens] himself says that it is pushing the limits of what’s doable in plastic — for more consistent webbing, he’d make some parts out of metal. But that’s quibbling; this thing is amazing.

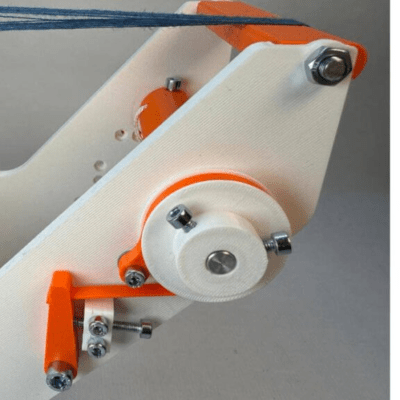

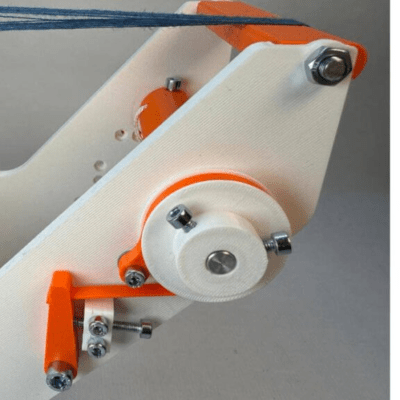

There are mechanical details galore here. For instance, check out the cam-chain that raises, holds, and lowers arms to make the pattern. Equally important are the adjustable friction brakes on the rollers that hold the warp, that create a controlled constant tension on the strings. (Don’t ask us, we had to Wikipedia it!) We can see that design coming in handy in some of our own projects.

There are mechanical details galore here. For instance, check out the cam-chain that raises, holds, and lowers arms to make the pattern. Equally important are the adjustable friction brakes on the rollers that hold the warp, that create a controlled constant tension on the strings. (Don’t ask us, we had to Wikipedia it!) We can see that design coming in handy in some of our own projects.

On the aesthetic front, the simple but consistent choice of three colors for gears, arms, and frame make the build look super tidy. And the accents of two-color printing on the end caps is just the cherry on the top.

This is no small project, with eight-beds-worth of printed parts, plus all the screws, bearings, washers, etc. The models are for pay, but if you’re going to actually make this, that’s just a tiny fraction of the investment, and we think it’s going to a good home.

We are still thinking of making [Fraens]’s vibratory rock tumbler design, but check out all of his work if you’re interested in nice 3D-printed mechanical designs.

Continue reading “Fraens’ New Loom And The Limits Of 3D Printing” →