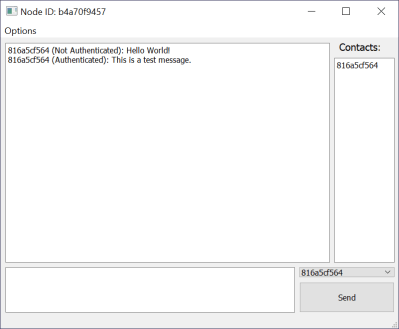

The Internet has allowed us to communicate more easily than ever before, and thanks to modern cell-phone networks, we don’t even have to be tied down to a hard line anymore. But what if you want something a little more direct? Maybe you’re in an area with no cell-phone coverage, or you don’t want to use public networks for whatever reason. For those cases, you might be interested in this Secure Communication Network project by [Thomas].

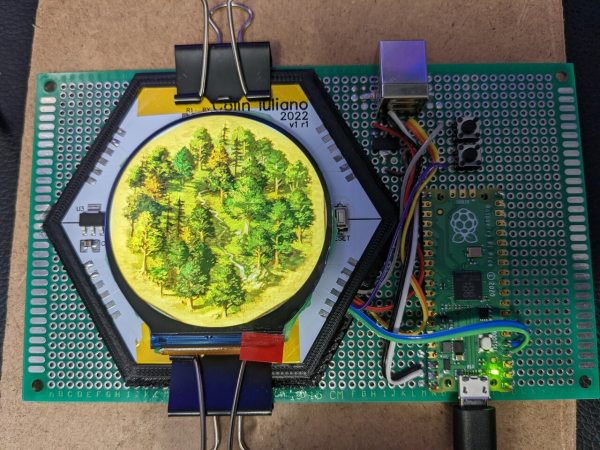

By leveraging the plug-and-play qualities of the Raspberry Pi 4 and the Adafruit LoRa Radio Bonnet, [Thomas] has been able to focus on the software side of this system that really turns these parts into something useful.

Rather than a simple point-to-point radio link, a mesh network is built up of any transceivers in range, extending the maximum distance a message can be sent, and building in resilience in case a node goes down. Each node is connected to a PC via Ethernet, and messages are distributed via a “controlled flooding” algorithm that aims to reduce unnecessary network congestion from the blind re-transmission of messages that have already been received.

Security is handled via RSA encryption with 256-byte public/private keys and additional SHA256 hashes for authentication.

The packet-size available through the LoRa device is limited to 256 bytes, of which 80 bytes are reserved for headers. To make matters worse, the remaining 176 bytes must contain encrypted data, which is almost always more lengthy than the raw message it represents. Because of this, longer messages are fragmented by the software, with the fragments sent out individually and re-assembled at the receiving end.

If you’re in need of a decentralized secure radio communications system, then there’s a lot to like about the project that [Thomas] has documented on his Hackaday.io page. He even includes an STL file for a 3D printed case. If you need to send more than text, then this Voice-over-LoRa Mesh Network project may be more your style.

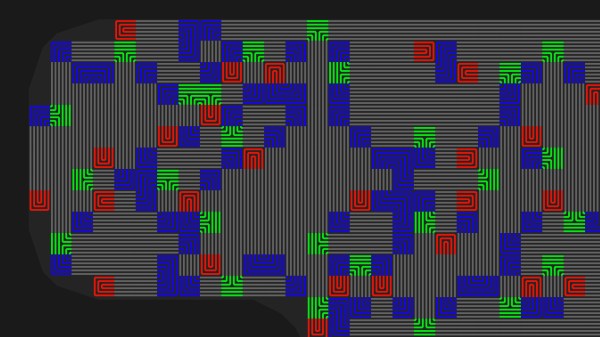

The idea is pretty simple, place traces very close to one another and it makes it impossible to drill into the case of a device without upsetting the apple cart. There are other uses as well, such as embedding them in adhesives that destroy the traces when pried apart. For [Sebastian’s] experiments he’s sticking with PCBs because of the ease of manufacture. His plugin lays down a footprint that has four pads to begin and end two loops in the mesh. The plugin looks for an outline to fence in the area, then uses a space filling curve to generate the path. This proof of concept works, but it sounds like there are some quirks that can crash KiCad. Consider

The idea is pretty simple, place traces very close to one another and it makes it impossible to drill into the case of a device without upsetting the apple cart. There are other uses as well, such as embedding them in adhesives that destroy the traces when pried apart. For [Sebastian’s] experiments he’s sticking with PCBs because of the ease of manufacture. His plugin lays down a footprint that has four pads to begin and end two loops in the mesh. The plugin looks for an outline to fence in the area, then uses a space filling curve to generate the path. This proof of concept works, but it sounds like there are some quirks that can crash KiCad. Consider