Apparently, there is a wrist-mounted device that delivers electric shocks to the wearer when it receives the appropriate command over Bluetooth. No, it’s not part of some kind of house arrest program. If you can believe it, the gadget is actually intended to help break bad habits or wake up exceptionally deep sleepers. We don’t know which of those problems [Becky Stern] has, but we’re glad to see she decided to take hers apart before the 21st century self-flagellation started.

Called the Pavlok and available for $180 USD from various online retailers, the device looks like a chunky fitness tracker. But in place of the screen that would show you how many steps you’ve taken or your current heart rate, there’s a lighting bolt button that you can press when you want to shock yourself. With the smartphone application, you can control the device remotely with a handy desktop widget that allows you to select the intensity of the shock. No, we aren’t making any of this up. Check out the video after the break to see it in action.

When [Becky] tried to take the Pavlok apart, she found that it was nearly impossible to handle it without inadvertently triggering a shock. So until she could get the case open and physically disconnect the battery, all she could do was turn the intensity down in the application and work through the occasional jolts from the device. We can only hope that more devices don’t adopt a similar sense of self-preservation.

When [Becky] tried to take the Pavlok apart, she found that it was nearly impossible to handle it without inadvertently triggering a shock. So until she could get the case open and physically disconnect the battery, all she could do was turn the intensity down in the application and work through the occasional jolts from the device. We can only hope that more devices don’t adopt a similar sense of self-preservation.

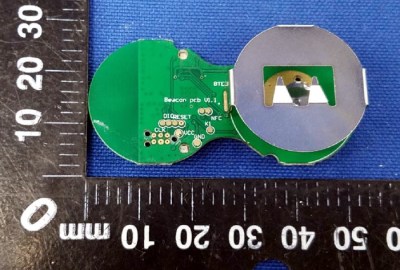

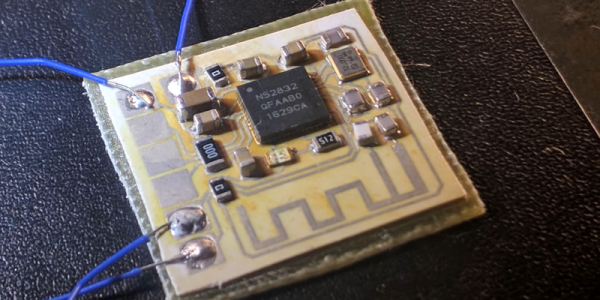

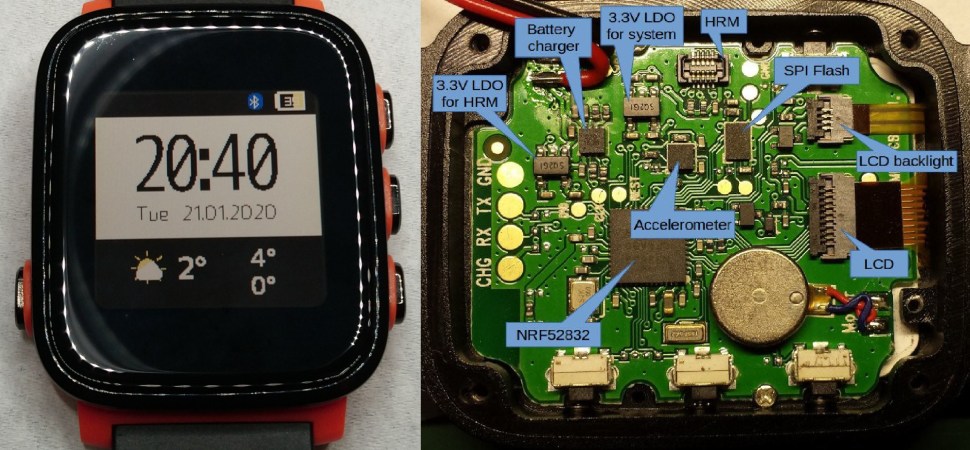

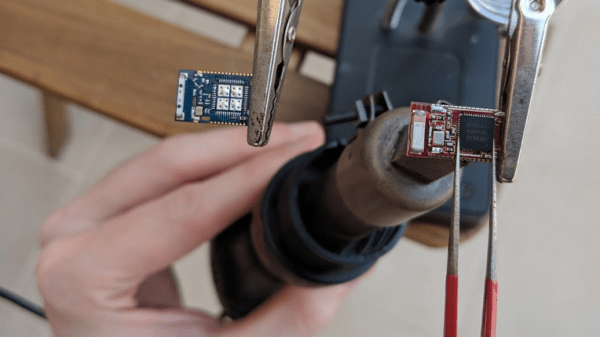

Once inside she found mainly the same kind of hardware you’d expect in a standard, non-masochistic, fitness wearable. There’s a nRF52832 Bluetooth SoC, a MMA8451Q accelerometer, a PCF85063A I2C RTC, and a FXAS21002C gyroscope. What you’re somewhat less likely to find inside your FitBit however is the LPR6235 coupled inductor and beefy capacitors which are used to build up a high-voltage charge from the standard 3.7 V LiPo battery.

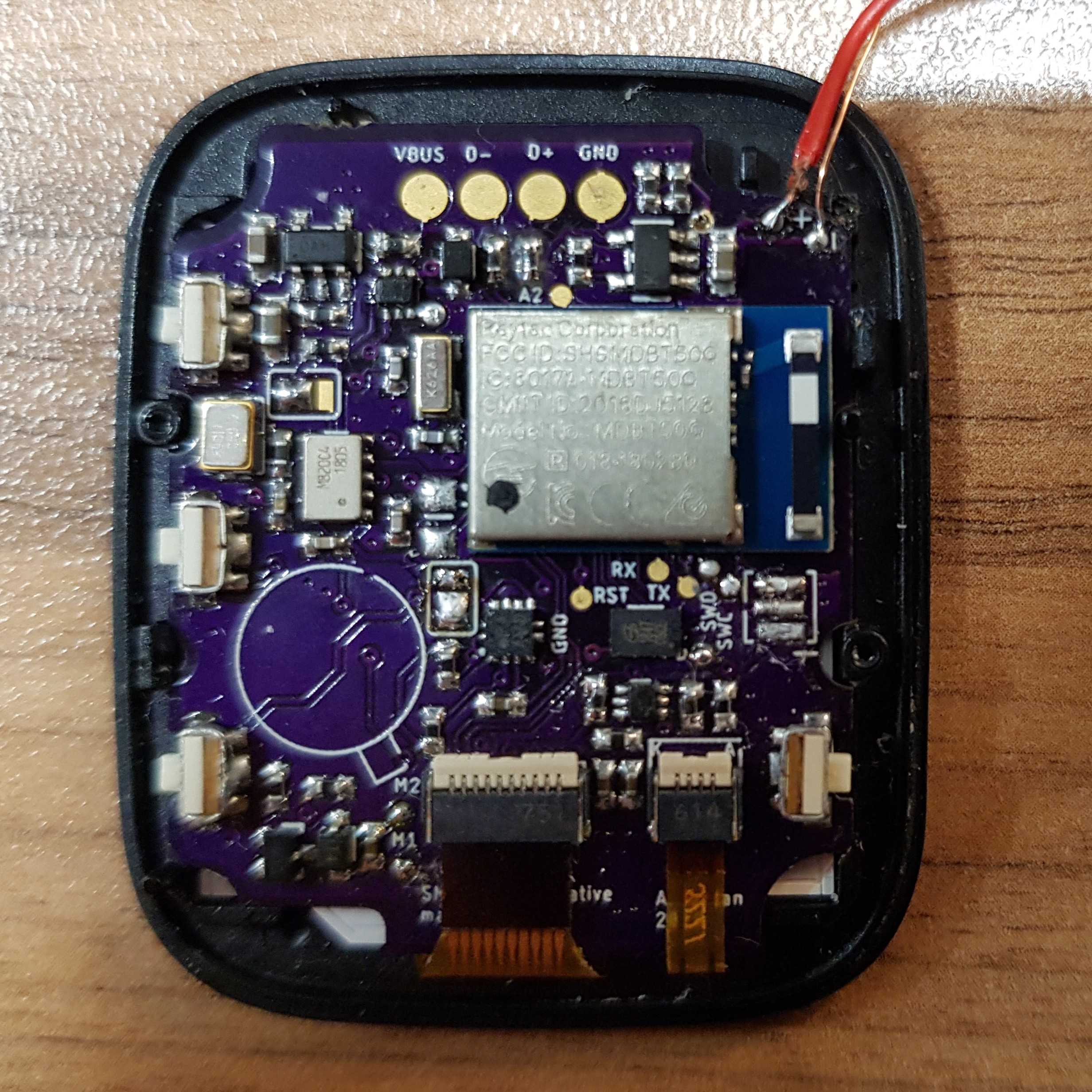

We’ve been very interested in the recent projects which are creating custom firmwares for commercially available fitness wearables, as it could be an express route to a hacker-friendly smartwatch. While the Pavlok has some compelling hardware, and the programming header [Becky] identified looks interesting, we don’t like the idea of being one misplaced if statement away from riding the lightning.

Continue reading “Pavlok Gets A Literally Shocking Teardown”

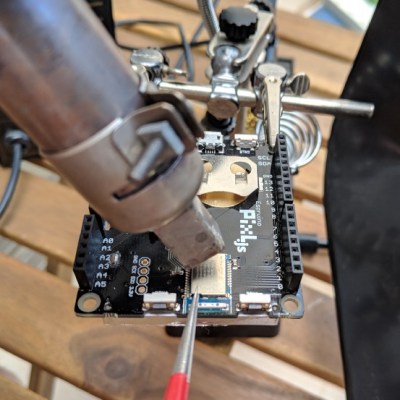

The board was the Pixl.js, an LCD board with the nRF52832 SoC with its ARM Cortex M4, RAM, flash, and Bluetooth LE. It also has a pre-installed Espruino JavaScript interpreter and of course the GPIO pins through which the damage was done.

The board was the Pixl.js, an LCD board with the nRF52832 SoC with its ARM Cortex M4, RAM, flash, and Bluetooth LE. It also has a pre-installed Espruino JavaScript interpreter and of course the GPIO pins through which the damage was done.