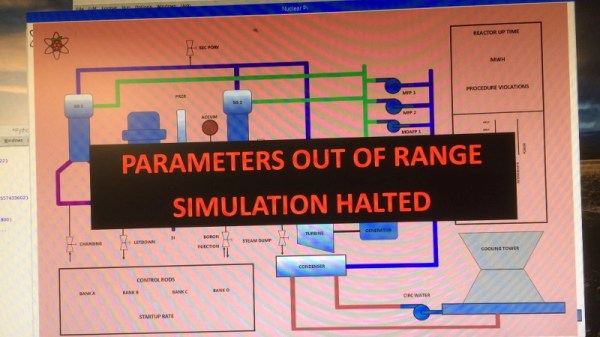

A nuclear power plant is large and complex, and one of the biggest reasons is safety. Splitting radioactive atoms is inherently dangerous, but the energy unleashed by the chain reaction that ensues is the entire point. It’s a delicate balance to stay in the sweet spot, and it requires constant attention to the core temperature, or else the reactor could go into meltdown.

Today, nuclear fission is largely produced with fuel rods, which are skinny zirconium tubes packed with uranium pellets. The fission rate is kept in check with control rods, which are made of various elements like boron and cadmium that can absorb a lot of excess neutrons. Control rods calm the furious fission boil down to a sensible simmer, and can be recycled until they either wear out mechanically or become saturated with neutrons.

Nuclear power plants tend to have large footprints because of all the safety measures that are designed to prevent meltdowns. If there was a fuel that could withstand enough heat to make meltdowns physically impossible, then there would be no need for reactors to be buffered by millions of dollars in containment equipment. Stripped of these redundant, space-hogging safety measures, the nuclear process could be shrunk down quite a bit. Continue reading “No-Melt Nuclear ‘Power Balls’ Might Win A Few Hearts And Minds”