There’s a seemingly unending list of modifications or upgrades you can make to a 3D printer. Most revolve around the mechanical side of things, many are simple prints or small add-ons. This upgrade is no small task: this 17-year-old hacker [Kai] took on designing and building his own 3D printer control motherboard, the Cheetah MX4 Mini.

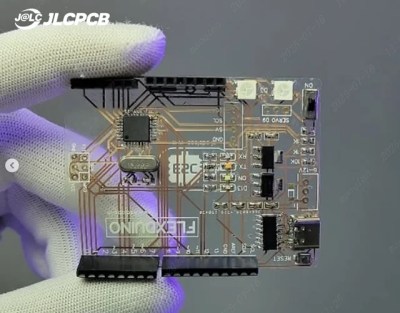

He started the build by picking out the MCU to control everything. For that, he settled on the STM32H743, a fast chip with tons of support for all the protocols he could ask for, even as he was still nailing down the exact features to implement. For stepper drivers, [Kai] went with four TMC stepstick slots for silent motor control. There are provisions for sensorless homing and endstops, support for parallel and serial displays, and both USB-C and microSD card slots for receiving G-code. It can drive up to three fans as well as two high-amperage loads, such as for the heated bed.

All these features are packed into a board roughly the size of a drink coaster. Thanks to the STM32H743, the Cheetah MX4 Mini supports both Marlin and Klipper firmware, a smart choice that lets [Kai] leverage the massive amount of work that’s already gone into those projects.

One of the things that stood out about this project is the lengths to which [Kai] went to document what he did. Check out the day-by-day breakdown of the 86 hours that went into this build; reading through it is a fantastic learning aid for others. Thanks [JohnU] for sending in this tip! It’s great to see such an ambitious project not only taken on and accomplished, but documented along the way for others to learn from. This is a fantastic addition to the other 3D printer controllers we’ve seen.