Gaussian Splats is a term you have likely come across, probably in relation to 3D scenery. But what are they, exactly? This blog post explains precisely that in no time at all, complete with great interactive examples and highlights of their strengths and relative weaknesses.

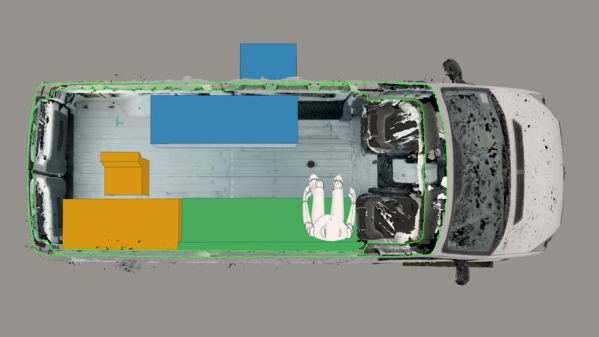

Gaussian splats are a lot like point clouds, except the points are each differently-shaped “splats” of color, arranged in such a way that the resulting 3D scene looks fantastic — photorealistic, even — from any angle.

All of the real work is in the initial setup of the splats into the scene. Once that work is done, viewing is the easy part. Not only are the resulting file sizes of the scenes small, but rendering is computationally simple.

There are a few pros and cons to gaussian splats compared to 3D meshes, but in general they look stunning for any kind of colorful, organic scene. So how does one go about making or using them?

That’s where the second half of the post comes in handy. It turns out that making your own gaussian splats is simply a matter of combining high-quality photos with the right software. In that sense, it has a lot in common with photogrammetry.

Even early on, gaussian splats were notable for their high realism. And since this space has more than its share of lateral-thinkers, the novel concept of splats being neither pixels nor voxels has led some enterprising folks to try to apply the concept to 3D printing.