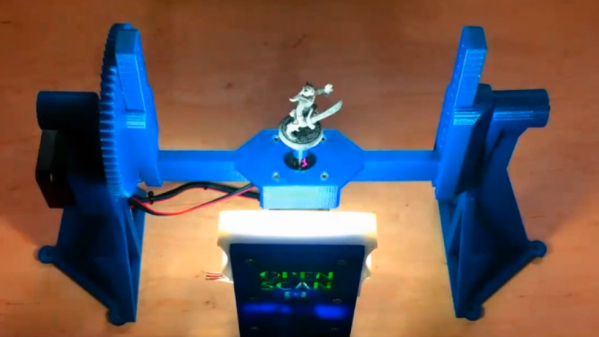

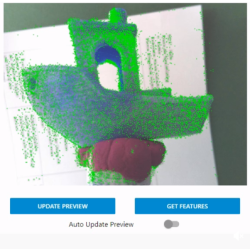

3D scanning and 3D printing may sound like a natural match for one another, but they don’t always play together as easily and nicely as one would hope. I’ll explain what one can expect by highlighting three use cases the average hacker encounters, and how well they do (or don’t) work. With this, you’ll have a better idea of how 3D scanning can meet your part design and 3D printing needs.

How Well Some Things (Don’t) Work

Most 3D printing enthusiasts sooner or later become interested in whether 3D scanning can make their lives and projects easier. Here are a three different intersections of 3D scanning, 3D printing, and CAD along with a few words on how well each can be expected to work.

| Goal | Examples and Details | Does it work? |

|---|---|---|

| Use scans to make copies of an object. |

|

Mostly yes, but depends on the object |

| Make a CAD model from a source object. |

|

Not Really |

| Digitize inconvenient or troublesome shapes. |

|

Yes, but it depends |

In all of these cases, one wants a 3D model of an object, and that’s exactly what 3D scanning creates, so what’s the problem? The problem is that not all 3D models are alike and useful for the same things.

Continue reading “What To Expect From 3D Scanning, And How To Work With It”