It comes as something of a shock that residents of the Lone Star State are suffering from rolling power blackouts in the face of an unusually severe winter. First off, winter in Texas? Second, isn’t it the summer heat waves that cause the rolling blackouts in that region?

Were you to mention Texas to a European, they’d maybe think of cowboys, oil, the hit TV show Dallas, and if they were European Hackaday readers, probably the semiconductor giant Texas Instruments. The only state of the USA with a secession clause also turns out to to have their own power grid independent of neighboring states.

Surely America is a place of such resourcefulness that this would be impossible, we cry as we watch from afar the red squares proliferating across the outage map. It turns out that for once the independent streak that we’re told defines Texas may be its undoing. We’re used to our European countries being tied into the rest of the continental grid, but because the Texan grid stands alone it’s unable to sip power from its neighbours in times of need.

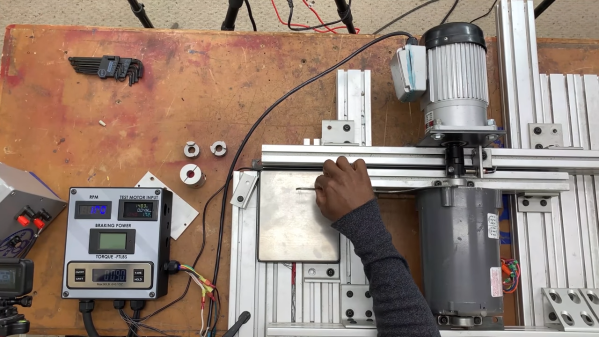

Let’s dive into the mechanics of maintaining an electricity grid, with the unfortunate Texans for the moment standing in as the test subject.