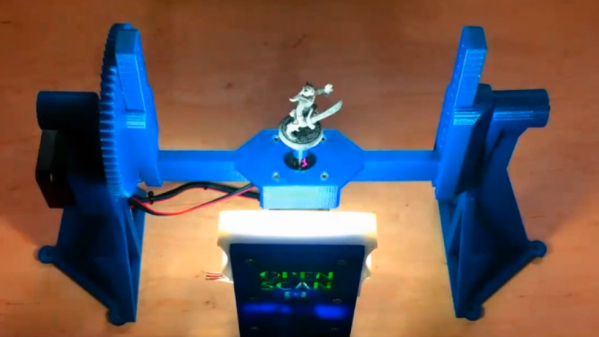

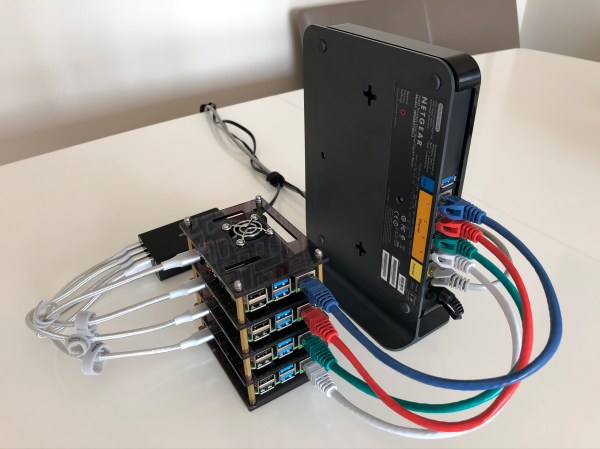

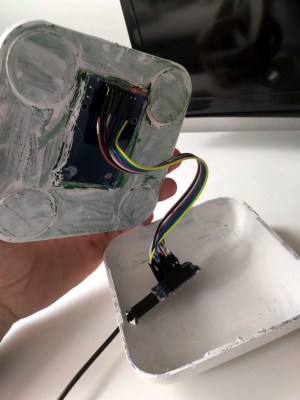

The OpenScan project has been updated quite a bit since its inception. OpenScan is an open source, Arduino or Raspberry Pi-based 3D scanner for small objects that uses 3D printed hardware and some common electronic components to create 3D scans using photogrammetry; a process by which a series of still images from different angles are used to create a 3D point cloud of an object, which can then be used to generate a 3D model.

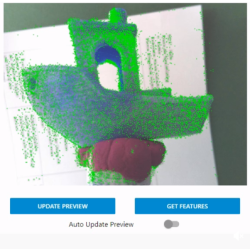

Photogrammetry is a somewhat involved process that relies on consistent conditions, so going through the whole process only to find out the results aren’t up to snuff can be tiresome. Happily, OpenScan offers some interesting new functions such as feature visualization via the web interface, which helps a user judge scan quality and make changes to optimize results without having to blindly cross their fingers quite so much. OpenScan remains a one-person project by [Thomas], who is clearly motivated to improve his design and we’re delighted to see it getting updates.

Embedded below is a video that walks through the installation and web interface. It’s a fairly long and comprehensive, but if you like you can skip directly to [Thomas] demonstrating the interface around the 8:22 mark, or watch it below. Interested in your own unit? [Thomas] has an e-shop for parts and the GitHub repository is right here; the project also has its own subreddit.

Continue reading “OpenScan 3D Scans All Of The (Small) Things”