If you’ve been hanging around Hackaday for a while, you’ve likely seen a few attempts to bridge the real world with the voxel paradise that is Minecraft. In the past, projects have connected physical switches to virtual devices in the game, or took chunks of the game’s blocky landscape and turned it into a 3D printable file. These were interesting enough endeavors, but fairly limited in their scope. They assumed you had an existing world or creation in Minecraft that you wanted to fiddle with in a more natural way, but didn’t do much for actually playing the game.

But “Physical Minecraft” presented at the 2018 World Maker Faire in New York, offered a unique way to bring players a bit closer to their cubic counterparts. Created by [Manav Gagvani], the physical interface has players use a motion detecting wand in combination with an array of miniature Minecraft blocks to build in the virtual world.

But “Physical Minecraft” presented at the 2018 World Maker Faire in New York, offered a unique way to bring players a bit closer to their cubic counterparts. Created by [Manav Gagvani], the physical interface has players use a motion detecting wand in combination with an array of miniature Minecraft blocks to build in the virtual world.

The wand even detects various gestures to activate an array of “Spells”, which are effectively automated build commands. For example, pushing the wand forward while making a twisting motion will automatically create a tunnel out of the selected block type. This not only makes building faster in the game, but encourages the player to experiment with different gestures and motions.

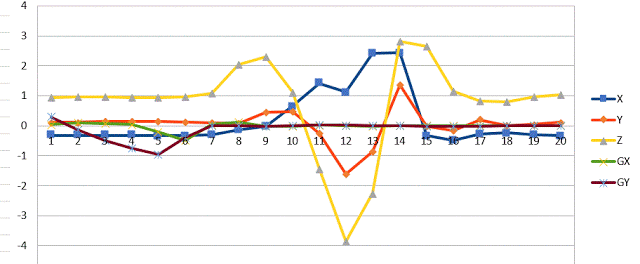

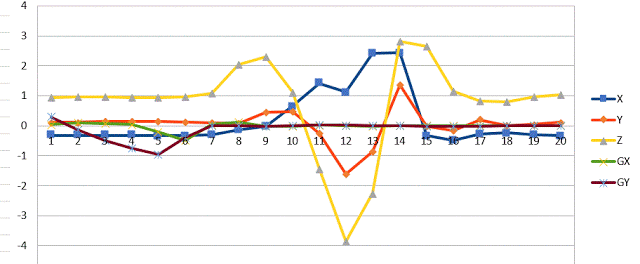

A Raspberry Pi 3 runs the game and uses its onboard Bluetooth to communicate with the 3D printed wand, which itself contains a MetaWear wearable sensor board. By capturing his own moves and graphing the resulting data with a spreadsheet, [Manav] was able to boil down complex gestures into an array of integer values which he plugged into his Python code. When the script sees a sequence of values it recognizes, the relevant commands get passed onto the running instance of Minecraft.

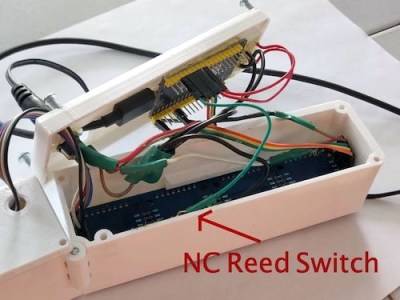

You might assume the wand itself is detecting which material block is attached to it, but that bit of magic is actually happening in the base the blocks sit on. Rather than trying to uniquely identify each block with RFID or something along those lines, [Manav] embedded an array of reed switches into the base which are triggered by the presence of the magnet hidden in each block.

You might assume the wand itself is detecting which material block is attached to it, but that bit of magic is actually happening in the base the blocks sit on. Rather than trying to uniquely identify each block with RFID or something along those lines, [Manav] embedded an array of reed switches into the base which are triggered by the presence of the magnet hidden in each block.

These switches are connected directly to the GPIO pins of the Raspberry Pi, and make for a very easy way to determine which block has been removed and installed on the tip of the wand. Things can get tricky if the blocks are put into the wrong positions or more than one block are removed at a time, but for the most part it’s an effective way to tackle the problem without making everything overly complex.

We’ve often talked about how kid’s love for Minecraft has been used as a way of getting them involved in STEM projects, and “Physical Minecraft” was a perfect example. There was a line of young players waiting for their turn on the wand, even though what they were effectively “playing” was the digital equivalent of tossing rocks. [Manav] would hand them the wand and explain the general idea behind his interface, reminding them that the blocks in the game are large and heavy: it’s not enough to just lower the wand, it needs to be flicked with the speed and force appropriate for the hefty objects their digital avatar is moving around.

Getting kids excited about hardware, software, and performing physically demanding activities at the same time is an exceptionally difficult task. Projects like “Physical Minecraft” show there can be more to playing games than mindless button mashing, and represent something of a paradigm shift for how we handle STEM education in an increasingly digital world.

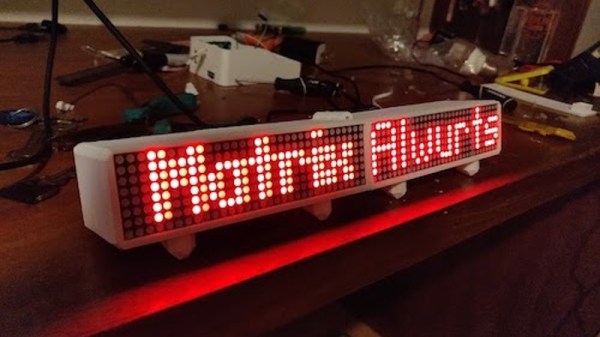

The clock uses eight individual 8 x 8 LED arrays contained in a 3D printed enclosure that hinges in the middle. When opened up the clock has a usable resolution of 8 x 64, and when its folded onto itself the resolution becomes 16 x 32.

The clock uses eight individual 8 x 8 LED arrays contained in a 3D printed enclosure that hinges in the middle. When opened up the clock has a usable resolution of 8 x 64, and when its folded onto itself the resolution becomes 16 x 32.