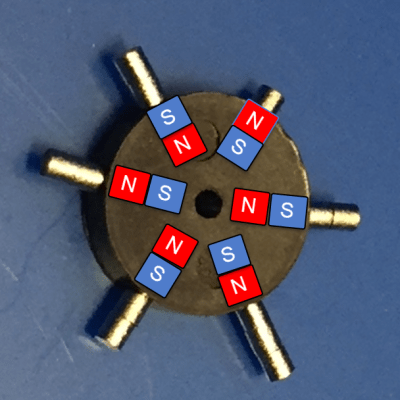

If you have a brushless motor, you have some magnets, a bunch of coils arranged in a circle, and theoretically, all the parts you need to build a rotary encoder. A lot of people have used brushless or stepper motors as rotary encoders, but they all seem to do it by using the motor as a generator and looking at the phases and voltages. For their Hackaday Prize project, [besenyeim] is doing it differently: they’re using motors as coupled inductors, and it looks like this is a viable way to turn a motor into an encoder.

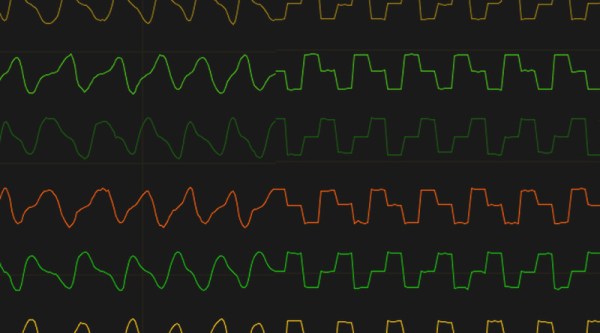

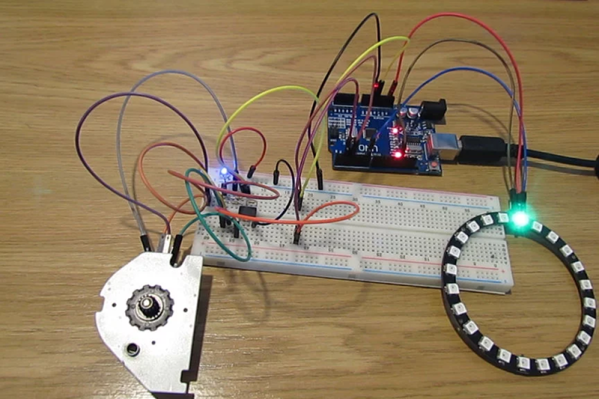

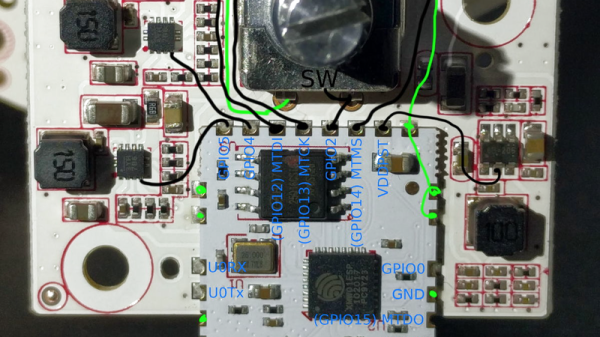

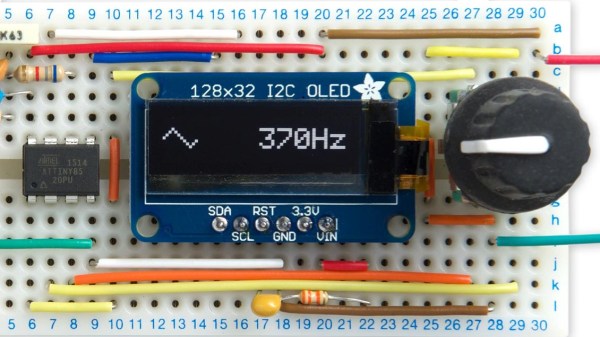

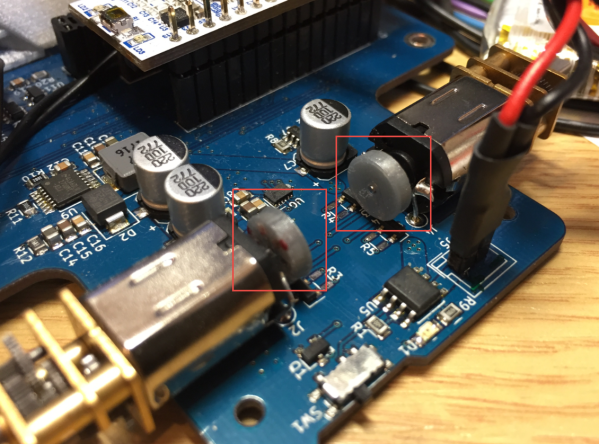

The experimental setup for this project is a Blue Pill microcontroller based on the STM32F103. This, combined with a set of half-bridges used to drive the motor, are really the only thing needed to both spin the motor and detect where the motor is. The circuit works by using six digital outputs to drive the high and low sided of the half-bridges, and three analog inputs used as feedback. The resulting waveform graph looks like three weird stairsteps that are out of phase with each other, and with the right processing, that’s enough to detect the position of the motor.

Right now, the project is aiming to send a command over serial to a microcontroller and have the motor spin to a specific position. No, it’s not a completely closed-loop control scheme for turning a motor, but it’s actually not that bad. Future work is going to turn these motors into haptic feedback controllers, although we’re sure there are a few Raspberry Pi robots out there that would love odometry in the motor. You can check out a video of this setup in action below.