On the technology spectrum, railroads would certainly seem to skew toward the brutally simplistic side of things. A couple of strips of steel, some wooden ties and gravel ballast to keep everything in place, some rolling stock with flanged wheels on fixed axles, and you’ve got the basics that have been moving freight and passengers since at least the 18th century.

But that basic simplicity belies the true complexity of a railway, where even just keeping the trains on the track can be a daunting task. The forces that a fully loaded train can exert on not only the tracks but on itself are hard to get your head around, and the potential for disaster is often only a failed component away. This became painfully evident with the recent Norfolk Southern derailment in East Palestine, Ohio, which resulted in a hazardous materials incident the likes of which no community is ready to deal with.

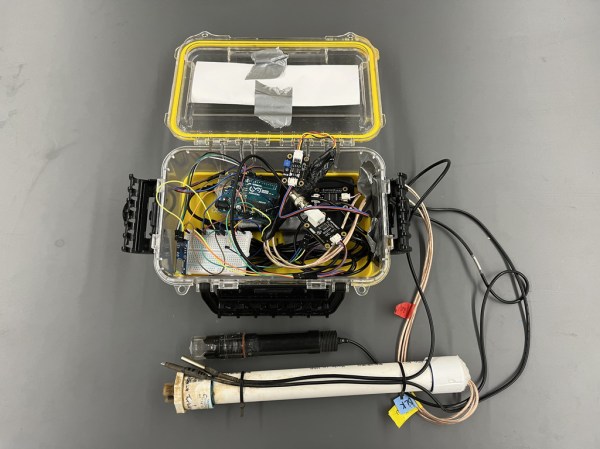

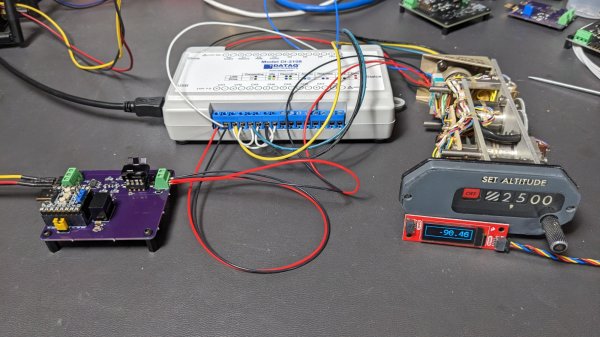

Given the forces involved, keeping trains on the straight and narrow is no mean feat, and railway designers have come up with a web of sensors and systems to help them with the task of keeping an eye on what’s going on with the rolling stock of a train. Let’s take a look at some of the interesting engineering behind these wayside defect detectors.

Continue reading “Feeling The Heat: Railway Defect Detection”