Teardowns are great because they let us peek not only at a product’s components, but also gain insight into the design decisions and implementations of hardware. For teardowns, we’re used to waiting until enthusiasts and enterprising hackers create them, so it came as a bit of a surprise to see Sony themselves share detailed teardowns of the new PlayStation VR2 hardware. (If you prefer the direct video links, Engineer [Takamasa Araki] shows off the headset, and [Takeshi Igarashi] does the same for the controllers.)

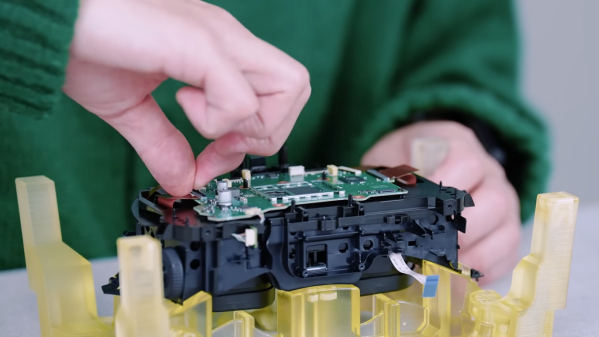

One particularly intriguing detail is the custom tool [Araki] uses to hold the headset at various stages of the disassembly, which is visible in the picture above. It looks 3D-printed and carefully designed, and while we’re not sure what it’s made from, it does have a strong resemblance to certain high-temperature SLA resins. Those cure into hard, glassy, off-yellow translucent prints like what we see here.

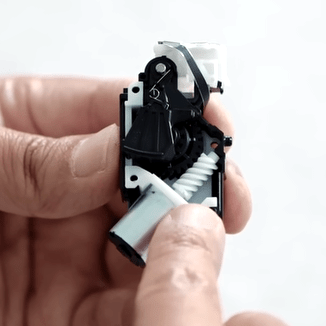

As for the controller, we get a good look at a deeply interesting assembly Sony calls their “adaptive trigger”. What’s so clever about it? Not only can it cause the user to feel a variable amount of resistance when pulling the trigger, it can even actively push back against one’s finger, and the way it works is simple and effective. It is pretty much the same as what is in the PS5 controller, so to find out all about how it works, check out our PS5 controller teardown coverage.

The headset and controller teardown videos are embedded just below. Did anything in them catch your interest? Know of any other companies doing their own teardowns? Let us know in the comments!

Continue reading “Watch Sony Engineers Tear Down Sony’s VR Hardware”