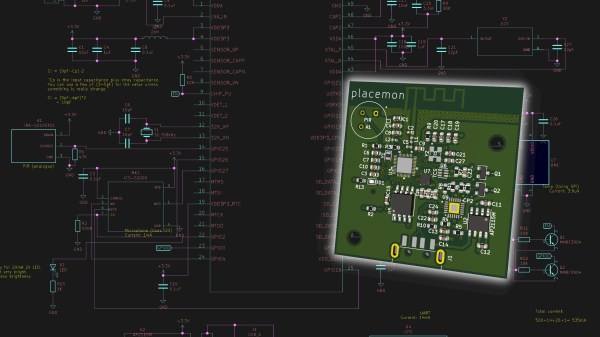

Abstraction is the core of nearly all progress in computing. Unless you are fabricating your own semiconductors and drawing wire, we all create with building blocks ranging from components like CPUs, to operating system functions, to specialized libraries. Just as you wouldn’t want to spend your time deblocking disk records or rendering fonts for output devices, you probably shouldn’t have to think too much about audio data. While there are some powerful audio processing libraries out there, a new embeddable language called SOUL (SOUnd Language) is now in version 1.0 and wants to help you create efficient code for processing audio.

The goal of SOUL is to target a runtime that can run on CPUs, but is better on DSPs. The code aims to be secure and real time with no pointers, garbage collection, and other things that typically interfere with audio processing or security.

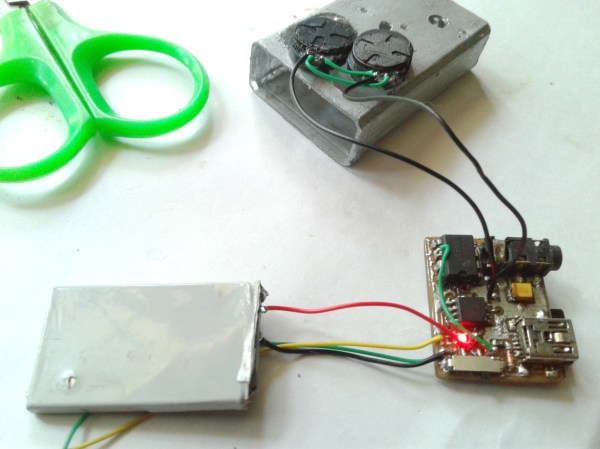

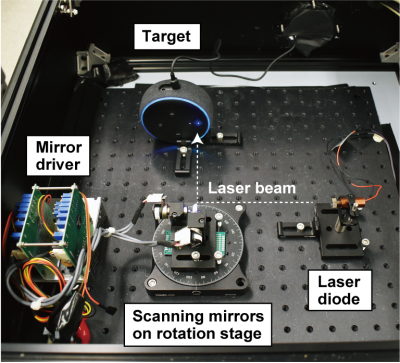

In one of the cooler hacks we’ve seen recently, a bunch of hacking academics at the University of Michigan researched the ability to flicker a laser at audible sound frequencies to see if they could remotely operate microphones simply by shining a light on them.

In one of the cooler hacks we’ve seen recently, a bunch of hacking academics at the University of Michigan researched the ability to flicker a laser at audible sound frequencies to see if they could remotely operate microphones simply by shining a light on them.  Knowles SPV0842LR5H. This attack is relatively easy to prevent; manufacturers would simply need to install screens to prevent light from hitting the microphones. For devices already installed in our homes, we recommend either putting a cardboard box over them or moving them away from windows where unscrupulous neighbors or KGB agents could gain access. This does make us wonder if MEMS mics are also vulnerable to radio waves.

Knowles SPV0842LR5H. This attack is relatively easy to prevent; manufacturers would simply need to install screens to prevent light from hitting the microphones. For devices already installed in our homes, we recommend either putting a cardboard box over them or moving them away from windows where unscrupulous neighbors or KGB agents could gain access. This does make us wonder if MEMS mics are also vulnerable to radio waves.