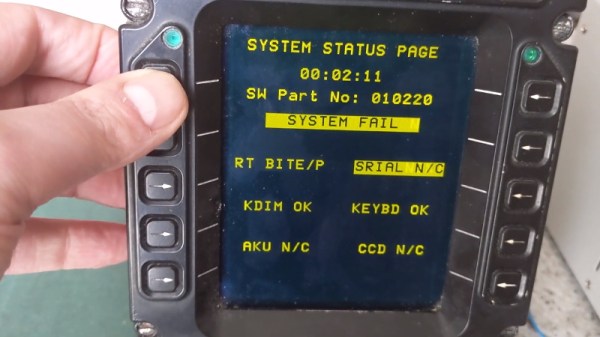

When [Kenneth Keiter] took apart his Starlink dish back in November, he did his best to explain the high-level functionality of the incredibly complex device in a video posted to his YouTube channel. It was a fascinating look at the equipment, but by his own admission, he wasn’t the right person to try and explain the nuances of how the phased array actually functioned. But he knew who could do the technology justice, which is why he shipped the dismembered dish over to [Shahriar Shahramian] of The Signal Path.

Don’t be surprised if you can’t quite wrap your head around his detailed analysis after your first viewing. You’ll probably have a few lingering questions after the second re-watch as well. But that’s OK, as [Shahriar] still has a few of his own. Even after cutting out a section of the dish and putting it under an X-ray, it’s still not completely clear how the SpaceX engineers managed to cram everything into such a tidy package. Though there seems to be no question that the $500 price for the early-access hardware is an absolute steal, all things considered.

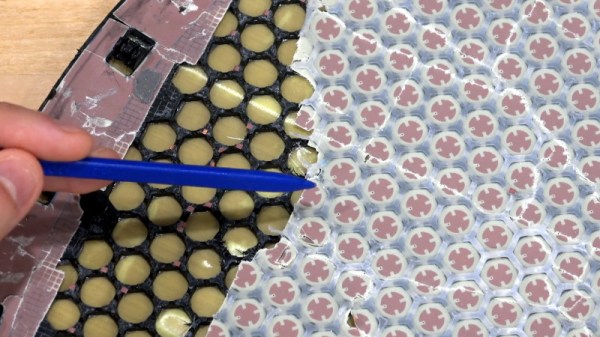

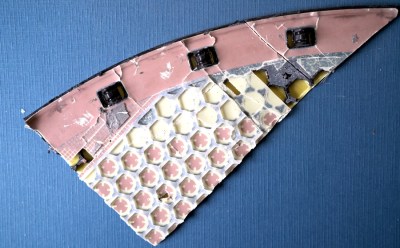

Most of the video is spent examining the stacked honeycomb construction of the phased antenna array, which as expected, holds a number of RF secrets if you know what to look for. Put simply, there’s no such thing as an insignificant detail to the trained eye. From the carefully sized injection molded spacer sheet that keeps the upper array a specific distance from the RF4-like radome, to the almost microscopic holes that have been bored through each floating patch to maintain equalized air pressure through the stack up, [Shahriar] picks up on fascinating details which might otherwise seem like arbitrary design decisions.

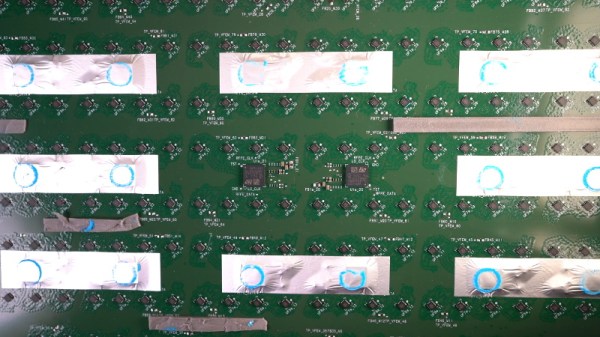

But a visual inspection will only get you so far. Eventually [Shahriar] has to cut out a slice of the PCB so he can fit it into the X-ray machine, but don’t feel too bad, the dish was long dead before he got his hands on it. While he hasn’t yet completed his full analysis, an initial examination indicates that each large IC and the eight chips surrounding it make up a 16 channel beam forming module. Each channel is further split into two RX and TX pairs, which provides the necessary right and left hand polarization. That said, he admits there’s some room for interpretation and that further work would be necessary before any hard conclusions could be made.

Between this RF analysis and the initial overview provided by [Kenneth], we’ve already learned a lot more about this device than many might have expected considering how rare and expensive the hardware is. While we admit it’s not immediately clear what kind of hijinks hardware hackers could get into once this device is fully understood, we’re certainly eager to find out.

Continue reading “Starlink Satellite Dish X-Rayed To Unlock RF Magic Inside”