The cost of tools and test equipment has largely been on the downward trend for years, making it now more affordable than ever to get into the hacking and making scene. This is particularly visible with something like the venerable oscilloscope: a piece of equipment that was near unobtainium for the home hacker a decade ago, you can now get digital pocket scope for as little as $20 USD. But there are still pieces of gear which haven’t quite hit the sort of prices we’d like to see.

A perfect example are thermal imaging cameras. The cheap ones are usually so low resolution they might as well just be thermometers, but the higher resolution ones can cost thousands. [Rob Scott] recently wrote in to tell us about a very promising middle ground, the HTI HT-A1. But he didn’t just point it out to us, he also tore it down and laid its internal’s bare for our entertainment. Now that’s our kind of introduction.

A perfect example are thermal imaging cameras. The cheap ones are usually so low resolution they might as well just be thermometers, but the higher resolution ones can cost thousands. [Rob Scott] recently wrote in to tell us about a very promising middle ground, the HTI HT-A1. But he didn’t just point it out to us, he also tore it down and laid its internal’s bare for our entertainment. Now that’s our kind of introduction.

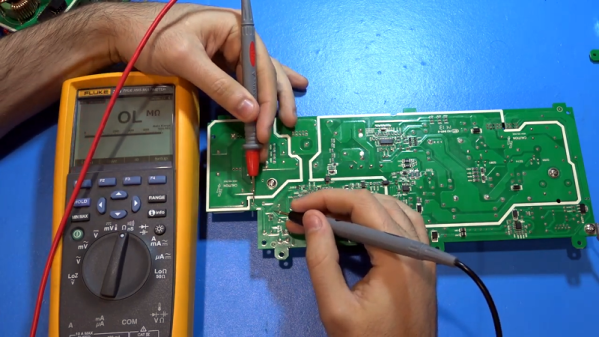

[Rob] walks us through the disassembly of the device, which is made unnecessarily difficult due to the fact that half the screws are hidden under a glued on screen bezel. That means a heat gun, a thin tool, and patience are in order if you want to get inside the device. It’s bad enough they use these kinds of construction techniques on modern smartphones, but at least they’re so thin that we can understand the reasoning. Why this chunky thing needs to resort to such measures is beyond us.

Eventually he cracks the HT-A1 open and is greeted with a single double-sided PCB. The top side is pretty much bare except for the buttons and the LCD display, and the flip side is largely just a breakout for a quad-core Allwinner A33 daughterboard. [Rob] theorizes this is to keep costs down by allowing reuse of the modular A33 board on other devices. Given the A33’s use in so many cheap tablets, it’s also possible HTI simply purchased these daughterboards as a drop-in component and designed their own board around it.

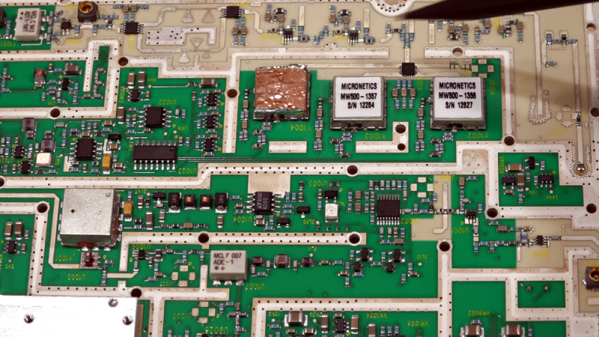

There’s not much else inside the HT-A1 beyond the rechargeable battery pack and thermal camera, both attached to the device’s rear panel. [Rob] noticed that the date on the thermal camera PCB is a full two years older than the date on the main PCB, leading one to wonder if HTI might have gotten a good deal on a bunch of these slightly outdated sensors and spun up a whole device around them.

The HT-A1 is high enough resolution that you can actually pick out individual components on a PCB, and at $400 USD is approaching a reasonable price point for the individual hacker. Which is not to say it’s cheap, but at least you get a useful tool for your money. We wouldn’t suggest you buy this device on a whim, but if you do a lot of diagnostic work, it might pay for itself after a couple repairs.

If that’s still a little too rich for your blood, we’ve covered a handful of DIY options which might better fit your budget.

Continue reading “Teardown Of A (Relatively) Cheap Thermal Camera” →