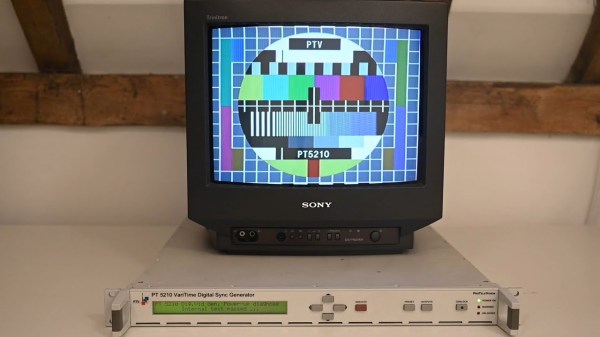

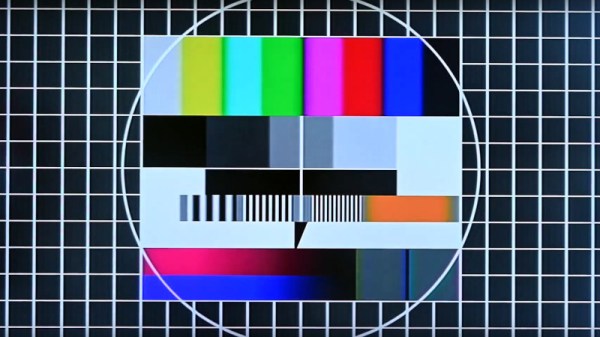

While most countries have switched to digital broadcasting, and most broadcasts themselves have programming on 24/7 now, it’s hard to remember the ancient times of analog broadcasts that would eventually stop sometime late at night, displaying a test pattern instead of infomercials or reruns of an old sitcom. They were useful for various technical reasons including calibrating the analog signals. Some test patterns were simply camera feeds of physical cards, but if you wanted the most accurate and reliable test patterns you’d need a Philips pattern generator which created the pattern with hardware instead, and you can build your own now because the designs for these devices were recently open-sourced. Continue reading “Recreating An Analog TV Test Pattern”

tv174 Articles

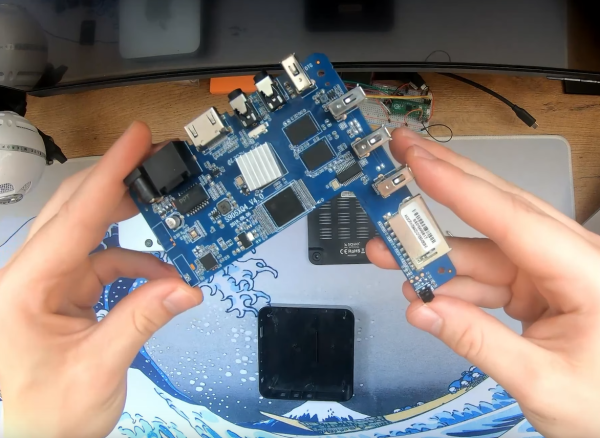

RetroPie, Without The Pi

The smart television is an interesting idea in theory. Rather than having the cable or satellite company control all of the content, a small computer is included in the television itself to host and control various streaming clients and other services. Assuming you have control of the software running on the computer, and assuming it isn’t turned into a glorified targeted advertising machine, this can revolutionize the way televisions are used. It’s even possible to turn a standard television into a smart TV with various Android devices, and it turns out there’s a lot more you can do with these smart TV contraptions as well.

With most of these devices, a Linux environment is included running on top of an ARM platform. If that sounds similar to the Raspberry Pi, it turns out that a lot of these old Android TV sets are quite capable of doing almost everything that a Raspberry Pi can do, with the major exception of GPIO. That’s exactly what [Timax] is doing here, but he notes that one of the major hurdles is the vast variety of hardware configurations found on these devices. Essentially you’d have to order one and hope that you can find all the drivers and software to get into a usable Linux environment. But if you get lucky, these devices can be more powerful than a Pi and also be found for a much lower price.

He’s using one of these to run RetroPie, which actually turned out to be much easier than installing a more general-purpose Linux distribution and then running various emulation software piecemeal. It will take some configuration tinkering get everything working properly but with [Timax] providing this documentation it should be a lot easier to find compatible hardware and choose working software from the get-go. He also made some improvements on his hardware to improve cooling, but for older emulation this might not be strictly necessary. As he notes in his video, it’s a great way of making use of a piece of electronics which might otherwise be simply thrown out.

A Look At Zweikanalton Stereo Audio And Comparison With NICAM

With how we take stereo sound for granted, there was a very long period where broadcast audio and television with accompanying audio track were in mono. Over the decades, multiple standards were developed that provide a way to transmit and receive two mono tracks, as a proper stereo transmission. In a recent video, [Matt] over at [Matt’s Tech Barn] takes a look at the German Zweikanalton (also known as A2 Stereo) standard, and compares it with the NICAM standard that was used elsewhere in the world.

Zweikanalton is quite simple compared to NICAM (which we covered previously), being purely analog with a second channel transmitted alongside the first. Since it didn’t really make much of a splash outside of the German-speaking countries, equipment for it is more limited. In this video [Matt] looks at the Philips PM 5588 and Rohde & Schwarz 392, analyzing the different modulations for FM, Zweikanalton and NICAM transmissions and the basic operation of the modulator and demodulator equipment.

An interesting aspect of these modulations are the visible sidebands, and the detection of which modulation is used. Ultimately NICAM’s only disadvantage compared to Zweikanalton was the higher cost of the hardware, but with increased technological development single-chip NICAM solutions like the Philips SAA7283 (1995) began to reduce total system cost and by the early 2000s NICAM was a standard feature of TV chipsets, just in time for analog broadcast television to essentially become irrelevant.

Continue reading “A Look At Zweikanalton Stereo Audio And Comparison With NICAM”

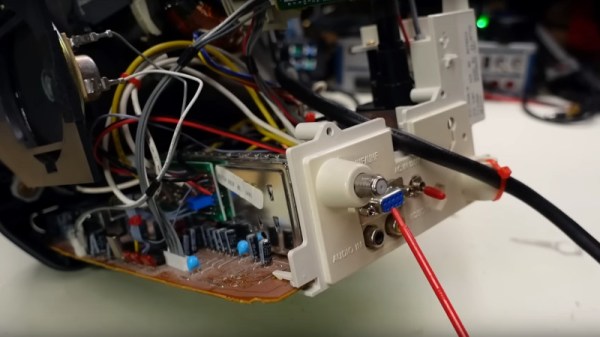

Old TV To RGB

As CRT televisions have faded from use, it’s become important for retro gaming enthusiasts to get their hands on one for that authentic experience. Alongside that phenomenon has been a resurgence of some of the hacks we used to do to CRT TV sets back in the day, as [Adrian’s Digital Basement] shows us when he adds an RGB interface to a mid-1990s Sony Trinitron.

Those of us lucky enough to have lived in Europe at the time were used to TVs with SCART sockets by the mid-1990s so no longer needed to plumb in RGB signals, but it appears that Americans were still firmly in the composite age. The TV might have only had a composite input, but this hack depends on many the video processor chips of the era having RGB input pins. If your set has a mains-isolated power supply then these pins can be hooked up with relative ease.

In the case of this little Sony, the RGB lines were used by the integrated on-screen display. He takes us through the process of pulling out these lines and interfacing to them, and comes up with a 9-pin D connector with the same pinout as a Commodore monitor, wired to the chip through a simple RC network and a sync level divider. There’s also a switch that selects RGB or TV mode, driving the OSD blanking pin on the video processor.

We like this hack just as much as we did when we were applying it to late-80s British TV sets, and it’s a great way to make an old TV a lot more useful. You can see it in the video below the break, so get out there and find a late-model CRT TV to try it on while stocks last!

Unsurprisingly, this mod has turned up here a few times in the past.

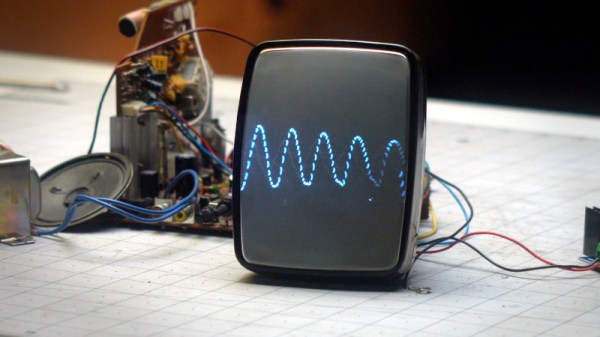

A CRT Audio Visualiser For When LEDs Just Won’t Do

It has been a recurring feature of consumer audio gear since the first magic eye tube blinked into life, to have some kind of visualization of the sound being played. Most recently this has meant an LED array or an OLED screen, but [Thomas] has gone one better than this with a CRT television converted to perform as a rudimentary oscilloscope.

The last generation of commonly available monochrome televisions were small 5″ CRT models made in China. They never received digital tuners, so as digital TV has become the norm they are now useless to most people. Thus they can often be found for pennies on the second-hand market.

[Thomas]’s hack involves gutting such a TV and retaining its circuitry, but disconnecting the line driver from the deflection yoke. This would normally leave a vertical line on the screen as it would then be moved only by the frame driver at 50 Hz for PAL or 60 Hz for NTSC. By connecting an audio loudspeaker amplifier to the line deflection yoke he gets that low quality oscilloscope. It would be of limited use as an instrument, but few others will have such a cool audio visualizer. He’s viewing the screen in a portrait orientation, we’d be tempted to rotate the yoke for a landscape view.

It’s worth pointing out as always that CRT TVs contain high voltages, so we’d suggest reading up on how to treat them with respect.

Continue reading “A CRT Audio Visualiser For When LEDs Just Won’t Do”

Robot Rebellion Brings Back BBC Camera Operators

The modern TV news studio is a masterpiece of live video and CGI, as networks vie for the flashiest presentation. BBC News in London is no exception, and embraced the future in 2013 to the extent of replacing its flesh-and-blood camera operators with robotic cameras. On the face of it this made sense; it was cheaper, and newsroom cameras are most likely to record as set range of very similar shots. A decade later they’re to be retired in a victory for humans, as the corporation tires of the stream of viral fails leaving presenters scrambling to catch up.

A media story might seem slim pickings for Hackaday readers, however there’s food for thought in there for the technically minded. It seems the cameras had a set of pre-programmed maneuvers which the production teams could select for their different shots, and it was too easy for the wrong one to be enabled. There’s also a suggestion that the age of the system might have something to do with it, but this is somewhat undermined by their example which we’ve placed below being from when the cameras were only a year old.

Given that a modern TV studio is a tightly controlled space and that detecting the location of the presenter plus whether they are in shot or not should not have been out of reach in 2013, so we’re left curious as to why they haven’t taken this route. Perhaps OpenCV to detect a human, or simply detecting the audio levels on the microphones before committing to a move could do the job. Either way we welcome the camera operators back even if we never see them, though we’ll miss the viral funnies.

Continue reading “Robot Rebellion Brings Back BBC Camera Operators”

A ’70s TV With ’20s Parts

Keeping older technology working becomes exponentially difficult with age. Most of us have experienced capacitor plague, disintegrating wire insulation, planned obsolescence, or even the original company failing and not offering parts or service anymore. To keep an antique running often requires plenty of spare parts, or in the case of [Aaron]’s vintage ’70s Sony television set, plenty of modern technology made to look like it belongs in a machine from half a century ago.

The original flyback transformer on this TV was the original cause for the failure of this machine, and getting a new one would require essentially destroying a working set, so this was a perfect candidate for a resto-mod without upsetting any purists. To start, [Aaron] ordered a LCD with controls (and a remote) that would nearly fit the existing bezel, and then set about integrating the modern controls with the old analog dials on the TV. This meant using plenty of rotary encoders and programming a microcontroller to do the translating.

There are plenty of other fine details in this build, including audio integration, adding modern video and audio inputs like HDMI, and adding LEDs to backlight the original (and now working) UHF and VHF channel indicators. In his ’70s-themed display wall, this TV set looks perfectly natural. If your own display wall spotlights an even older era, take a look at some restorations of old radios instead.