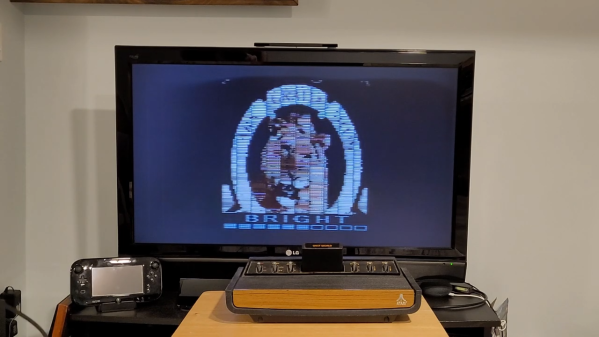

When you think 1080p video, you probably don’t think STM32 microcontroller. And yet! [Gabriel Cséfalvay] has pulled off just that through the creative use of on-chip peripherals. Sort of.

The build is based around the STM32L4P5—far from the hottest chip in the world. Depending on the exact part you pick, it offers 512 KB or 1 Mbyte of flash memory, 320 KB of SRAM, and runs at 120 MHz. Not bad, but not stellar.

Still, [Gabriel] was able to push 1080p at a sort of half resolution. Basically, the chip is generating a 1080p widescreen RGB VGA signal. However, to get around the limited RAM of the chip, [Gabriel] had to implement a hack—basically, every pixel is RAM rendered as 2×2 pixels to make up the full-sized display. At this stage, true 1080p looks achievable, but it’ll be a further challenge to properly fit it into memory.

Output hardware is minimal. One pin puts out the HSYNC signal, another handles VSYNC. The same pixel data is clocked out over R, G, and B signals, making all the pixels either white or black. Clocking out the data is handled by a nifty combination of the onboard DMA functionality and the OCTOSPI hardware. This enables the chip to hit the necessary data rate to generate such a high-resolution display.

There’s more work to be done, but it’s neat to see [Gabriel] get even this far with such limited hardware. We’ve seen others theorize similar feats on chips like the RP2040 in the Pi Pico, too. Video after the break.

Continue reading “Doing 1080p Video, Sort Of, On The STM32 Microcontroller”