No matter what they’re flying, good pilots have a “feel” for their aircraft. They know instantly when something is wrong, whether by hearing a strange sound or a feeling a telltale vibration. Developing this sixth sense is sometimes critical to the goal of keeping the number of takeoff equal to the number of landings.

The same thing goes for non-traditional aircraft, like paragliders, where the penalty for failure is just as high. Staying out of trouble aloft is the idea behind this paraglider line tension monitor designed by pilot [Andre Bandarra]. Paragliders, along with their powered cousins paramotors, look somewhat like parachutes but are actually best described as an inflatable wing. The wing maintains its shape by being pressurized by air coming through openings in the leading edge. If the pilot doesn’t maintain the correct angle of attack, the wing can depressurize and collapse, with sometimes dire results.

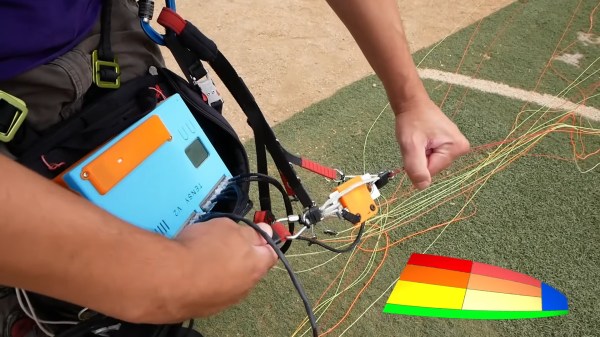

Luckily, most pilots eventually develop a feel for collapse, sensed through changes in the tension of the lines connecting the wing to his or her harness. [Andre]’s “Tensy” — with the obligatory “McTenseface” surname — that’s featured in the video below uses an array of strain gauges to watch to the telltale release of tension in the lines for the leading edge of the wing, sounding an audible alarm. As a bonus, Tensy captures line tension data from across the wing, which can be used to monitor the performance of both the aircraft and the pilot.

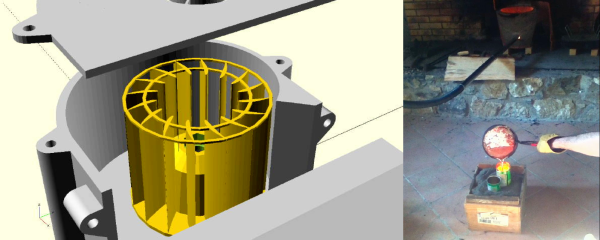

There are a lot of great design elements here, but for our money, we found the lightweight homebrew strain gauges to be the real gem of this design. This isn’t the first time [Andre] has flown onto these pages, either — his giant RC paraglider was a big hit back in January.

Continue reading “Custom Strain Gauges Help Keep Paraglider Aloft”