[CNCDan] previously dabbled with Raspberry Pi CM4-powered gaming handhelds but was itching for something more powerful. Starting in May 2023, he embarked on building an Intel NUC7i5BNK-powered handheld dubbed NucDeck.

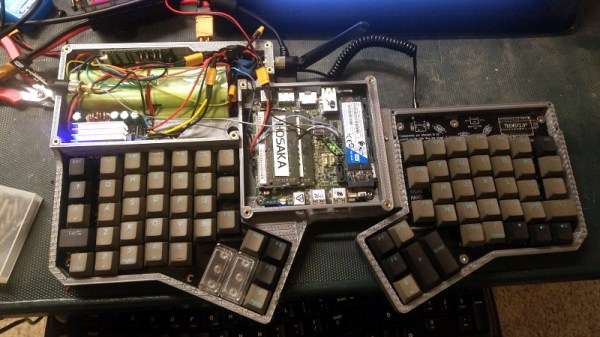

As he goes over the feature list, it sounds like a commercially available console. A 1024 x 600 screen provides a good balance of fidelity and performance. Stereo-chambered speakers provide good front-facing sound. Two thumbsticks with gyro aim assist, two hall effect triggers, and many buttons round out the input. Depending on the mode, the Raspberry Pi Pico provides input as it can emulate a mouse and keyboard or a more traditional gamepad. A small OLED screen shows battery status, input mode, and other options. This all fits on four custom PCBs, communicating over I2C. 6000 mAh of battery allows for a decent three hours of run time for simpler emulators and closer to an hour for more modern games.

The whole design is geared around easily obtainable parts, and the files are open-source and on GitHub with PDFs and detailed build instructions. We see plenty of gorgeous builds here on Hackaday, but everything from the gorgeous translucent case to the build instructions screams how much time and love has been put into this. Of course, we’ve seen some exciting hacks with the steam deck (such as this one emulating a printer), so we can only imagine what sort of things you can do once you add any new hardware features you’d like.

Continue reading “The Best Kind Of Handheld Gaming Is Homemade”