For the last five years or so, Nintendo has been selling the 3DS, the latest in a long line of handheld consoles. Around two years ago, Nintendo announced the New Nintendo 3DS, with a faster processor and a few other refinements. The new 3DS comes in two sizes: normal and XL. You can buy the XL version anywhere in the world, but Nintendo fans in North America cannot buy the normal version.

[Stephen] didn’t want the jumbo-sized New 3DS XL, both because it’s too large for his pockets, and because there are no fancy cases for the XL. His solution? Creating a US non-XL 3DS with god-like soldering skills.

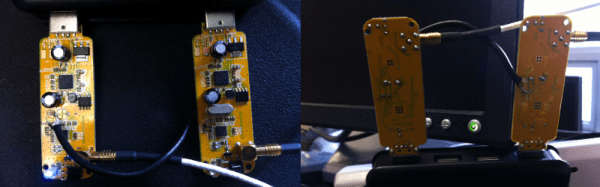

In manufacturing the XL and non-XL versions of the 3DS, Nintendo didn’t change much on the PCBs. Sure, the enclosure is different, but electronically there are really only two changes: the eMMC storage and the Nintendo processor. 3DS are region-locked, so simply swapping out the boards from a normal 3DS to an XL 3DS wouldn’t work; [Stephen] would also like to play US games on his modded console. That leaves only one option: desoldering two chips from a US XL and placing them on the board from a Japanese 3DS.

With a board preheater and heat gun, [Stephen] was able to desolder the eMMC chip off both boards. Of course this meant the BGA balls were completely destroyed in the process, which means reballing the package with solder bits only 0.3mm in diameter. With the US eMMC transplanted to the Japanese board, [Stephen] ended up with an error message that suggested the processor was reading the memory. Progress, at least.

[Stephen] then moved on to the processor. This was a nightmare of a 512 pin BGA package, with 512 pins that needed a tiny dot of solder placed on them. Here, sanity gave way and [Stephen] called up a local board and assembly house. They agreed to solder the chip onto the board and do an x-ray inspection. With the professional rework done, [Stephen] assembled his new US non-XL 3DS, and everything worked. It’s the only one in the world, and given the effort required to make these mods, we’re expecting it to remain the only one for a very long time.