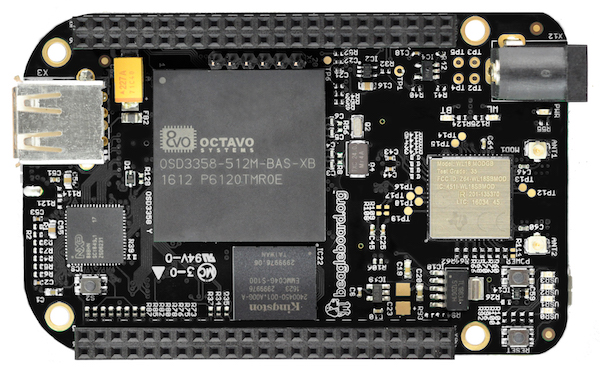

The BeagleBone is a very popular single board computer, best applied to real-time applications where you need to blink LEDs really, really fast. Over the years, the BeagleBone has been used for stand-alone CNC controllers, the brains behind very large LED installations, and on rare occasions has been used to drive CRTs. If you just want a small Linux board, get a Pi. If you want to do something interesting with hardware, get a BeagleBone.

The BeagleBone ecosystem has grown a lot in the last year, from the wireless and Grove connector equipped BeagleBone Green, the robotics-focused BeagleBone Blue, the Zoolander-inspired Blue Steel. Now there’s a new BeagleBone, built around a very interesting System on Module introduced earlier this year.

The new board is called the BeagleBone Black Wireless, and it brings to the table all you know and love about the BeagleBone. There’s a 1GHz ARM355x with two 32-bit 200MHz PRUs for the real-time pin toggling. RAM is set at 512MB, with 4GB of eMMC Flash and Debian pre-installed, and a microSD card for larger storage options. The new feature is wireless connectivity: a TI WiFi and Bluetooth module with provisions for 802.11s replaces the old Ethernet connector.

Taken at face value, the new BeagleBone Black Wireless deserves a mention — it’s a BeagleBone with wireless — but isn’t particularly noteworthy. But when you get to the gigantic brick of resin dropped squarely in the middle of the board does the latest device in the BeagleBone family become very, very interesting. The System on Module for this version of the BeagleBone is the BeagleBone On A Chip released a few months ago. The Octavo Systems OSD335x is, quite literally, a BeagleBone on a chip. It’s a BGA with big balls, making it solderable with hand-applied solder paste and a toaster oven reflow conversion. In fact, the BeagleBone Wireless was designed by [Jason Kridner] in Eagle as a 6-layer board. It’s still a bit beyond the standard capabilities of OSHPark, but the design can still be cut down, and shows how this BeagleBone on a Chip can be applied to other Open Hardware projects.