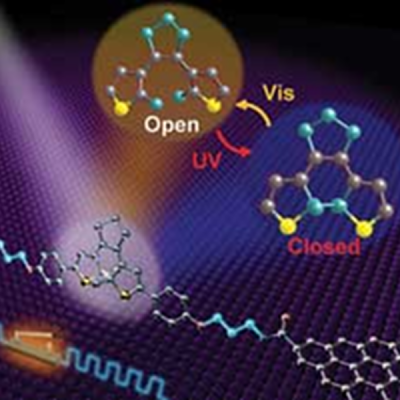

Everything is getting smaller all the time. Computers used to take rooms, then desks, and now they fit in your pocket or on your wrist. Researchers that investigate light sensors have known that individual diarylethene molecules can exist in two states: one where it conducts electricity and one where it doesn’t. A visible photon causes the molecule to be electrically open and ultraviolet causes it to close. But there’s a problem.

Placing electrodes on the molecule interferes with the process. Depending on the kind of electrode, the switch will get stuck in the on or off position. Researchers at Peking University in Beijing determined that placing some buffering material between the molecule and the electrodes would reduce the interference enough to maintain correct operation. What’s more the switches remain operable for a year, which is unusually long for this kind of construct.

Placing electrodes on the molecule interferes with the process. Depending on the kind of electrode, the switch will get stuck in the on or off position. Researchers at Peking University in Beijing determined that placing some buffering material between the molecule and the electrodes would reduce the interference enough to maintain correct operation. What’s more the switches remain operable for a year, which is unusually long for this kind of construct.

Using chemical vapor deposition and electron beam lithography, the team produced over 40 working single molecule switches. These devices could be useful in optical computing and other applications. Future work will include developing multilevel switches comprised of multiple molecules.

If you want something more macroscopic, you might try using an LED to sense light. A switch is fine, but sometimes you want to generate a signal.