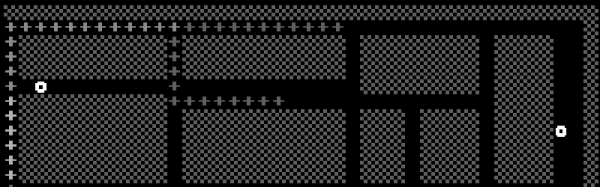

Walkers like the Strandbeest are favorites due in part to their smooth design and fluid motion, but [Leandro] is going a slightly different way with Octo, an octopodal platform for exploring rough terrain. Octo is based on the Klann linkage which was developed in 1994 and intended to act as an alternative to wheels because of its ability to deal with rough terrain. [Leandro] made a small proof of concept out of soldered brass and liked the results. The next version will be larger, made out of aluminum and steel, and capable of carrying a payload.

The Strandbeest and Octo have a lot in common but differ in a few significant ways. Jansen’s linkage (which the Strandbeest uses) uses eight links per leg and requires relatively flat terrain. The Klann linkage used by Octo needs only six links per leg, and has the ability to deal with rougher ground.

[Leandro] didn’t just cut some parts out from a file found online; the brass proof of concept was drawn up based on an animation of a Klann linkage. For the next version, [Leandro] used a simulator to determine an optimal linkage design, aiming for one with a gait that wasn’t too flat, and maximized vertical rise of the leg to aid in clearing obstacles.

We’ve seen the Klann linkage before in a LEGO Spider-bot. We’re delighted to see [Leandro]’s Octo in the ring for the Wheels, wings, and walkers category of The Hackaday Prize.