Congratulations and thank you go to Theodore Yapo for authoring the first paper to complete the peer review process for the Hackaday Journal. You can read the standalone paper here; it will be included in the first volume of the Hackaday Journal officially released later this year.

The Hackaday Journal is an open access, peer reviewed journal that seeks to ensure hard-won domain knowledge is preserved and made available for the benefit of all. Before jumping into Ted’s topic, please take a moment to consider submitting your own paper for the journal.

Paper Submissions Wanted

We have other submissions in the pipleline now but we still need more papers to round out the first volume of the Hackaday Journal. Please consider authoring a paper on any creative research, engineering, or entertaining discovery in the areas of interest to the Hackaday community. The full name of our journal is the Hackaday Journal of What You Don’t Know — it will be a tome of infinite appeal to any who seek to broaden their minds in the engineering space. But for that to happen we need you to share your knowledge.

We are in an age of unparalleled opportunity for individuals and small teams to make interesting discovery. You should not need to be working on a degree to have your findings published, but of course students and faculty are encouraged to submit their papers. Do not hesitate to get in touch with us about topics you want to write about.

Scalar Network Analyzer Leakage Correction by Theodore Yapo

The title of Ted’s paper is a mouthful and the subject material wades into radio frequency knowledge with gusto. We applaud him, and the peer reviewers, for the attention to detail while moving toward publication.

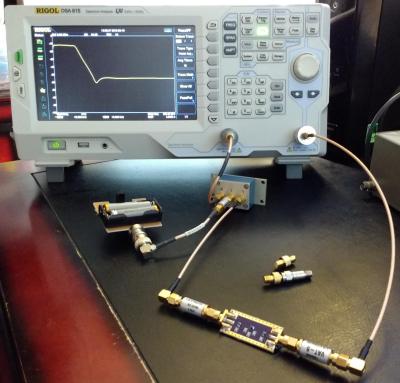

In his work, Ted finds an interesting opportunity to get more performance out of relatively inexpensive bench equipment used to characterize RF components. This task is often reserved for Vector Network Analyzers (VNA) but with a heafty price tag these tools aren’t available to everyone. Spectrum Analyzers with Tracking Generators (SA/TG) have come onto the market, but especially with early versions, there is a leakage problem that causes inaccuracy. Ted found a simple technique that can correct for the leakage.

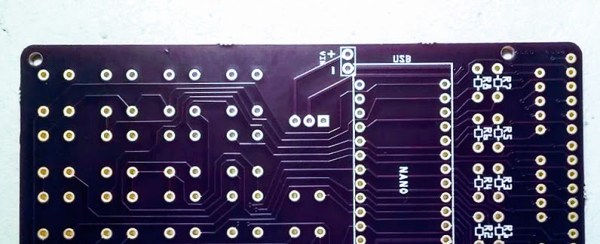

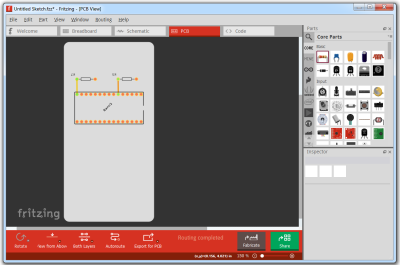

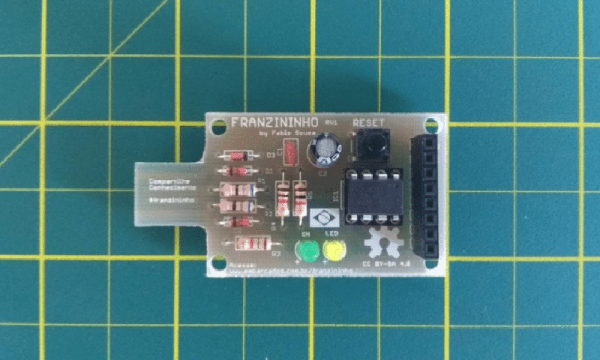

The solution is based on phase shifting the measurement. Starting with a properly calibrated machine, Ted uses a small board he built to electronically shift the phase of the Tracking Generator where the leakage is a problem. The signal is first measured, then measured again with a phase shift of 180 degrees. This effectively cancels out the error while preserving the signal being measured.

This paper goes into great technical detail in the RF domain. It is worth noting that the Hackaday Journal is open to discovery on multiple topics and levels of complexity. Don’t let what you think is a simple, useful idea go unpublished. We’re interested in a wide range of the simple, the obscure, and the frighteningly technical as long as the ideas of both novel and well supported.

This is Your Journal

You, yes you reading this right now, embody a movement of inventive and curious people working both inside and outside of formal academic structures. This is our time to contribute to the knowledge base of humanity. Pour yourself a refreshing beverage, saddle up your headphones, crack those knuckles, and let the writing process begin. Let us now what we don’t know. Submit your paper now.

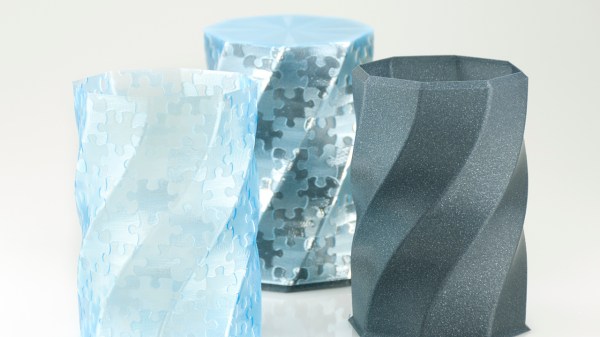

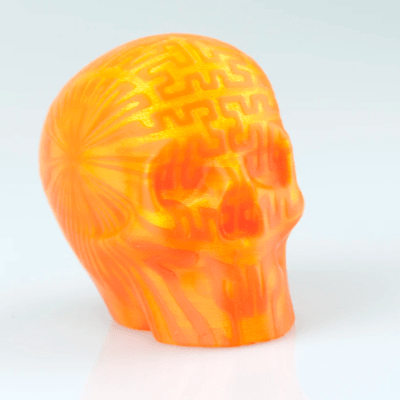

At its core, the technique is straightforward: skin an image onto a 3D print by varying the print speed in specific locations and, thereby, varying just how much plastic oozes out of the nozzle. While the concept seems simple, the result is stunning.

At its core, the technique is straightforward: skin an image onto a 3D print by varying the print speed in specific locations and, thereby, varying just how much plastic oozes out of the nozzle. While the concept seems simple, the result is stunning.