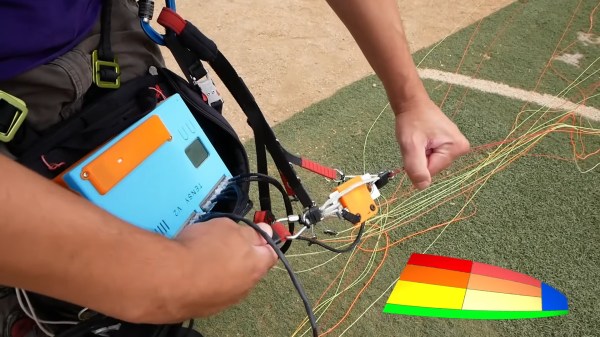

The dream of taking to the air has probably ensnared more than a few of us, but for most it remains elusive as the safety, regulatory, and training frameworks surrounding powered flight make it not an endeavour for the faint-hearted. [Justine Haupt] has probably delivered the simplest possible powered aircraft with her Blimp Drive, a twin-prop electric add-on for her paragliding rig that allows her to self-launch, and to sustain her flights while soaring.

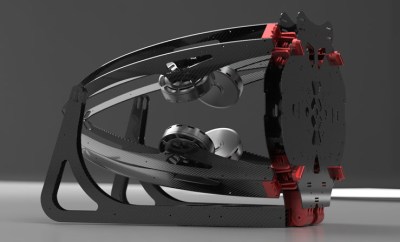

It takes the form of a carbon-fibre tube with large drone motors and props U-bolted to each end, and a set of brackets in the centre of laid carbon fibre over 3D-printed forms to which the battery and paraglider harness are attached. The whole thing is lightweight and quiet, and because of the two contra-rotating propellers it also doesn’t possess the torque issues that would affect a single propeller craft.

We’re not fliers or paragliders here at Hackaday, so our impression of the craft in use doesn’t come from the perspective of a pilot. But its simplicity and ease of getting into the air looks to be unmatched by anything else, and we have to admit a tinge of envy as in the video below the break she flies over the beach that’s her test site.

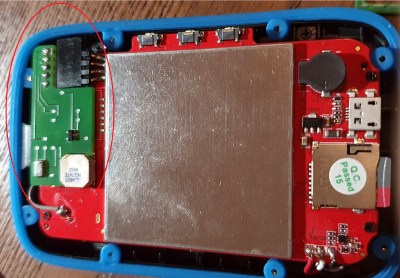

If you recognise Justine from past Hackaday articles, you’re on the right track. Probably most memorable is her rotary cellphone.

Continue reading “Is There A Simpler Aircraft Than This Electric Paramotor?”