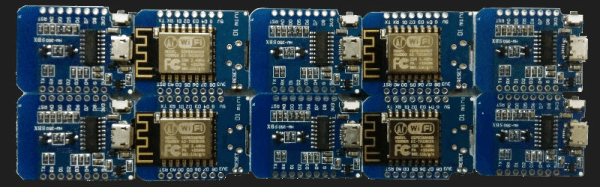

As far as ESP8266 boards go, the WeMos D1 Mini is a great choice if you’re looking to get started with hackerdom’s microcontroller du jour. It’s small, well supported, and can be had ridiculously cheap. Often going for as little as $3 USD each, we buy the things in bulk just to have spares on hand. But that’s not to say it’s a perfect board. For one, it lacks the customary mounting holes which would allow you to better integrate it into finished products.

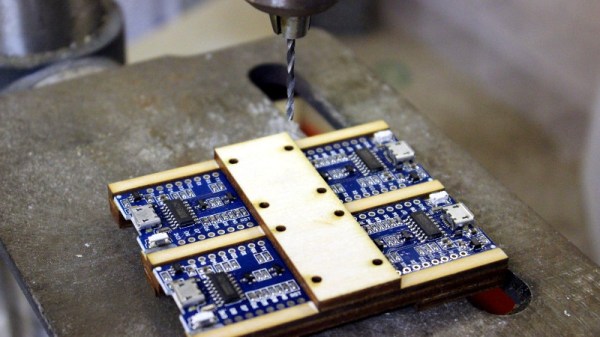

This minor annoyance was enough to spring [Martin Raynsford] into action. He noticed there was some open area on the D1 Mini’s PCB where it seemed he could drill through to add his own mount points, but of course popping holes in a modern PCB can be risky business. There’s not a lot of wiggle room between success and heartbreak, and it’s not like the diminutive D1 Mini is that easy to hold down to begin with. So he designed a laser-cut jig to allow him to rapidly add mounting holes to his D1 Mini’s assembly line style.

This minor annoyance was enough to spring [Martin Raynsford] into action. He noticed there was some open area on the D1 Mini’s PCB where it seemed he could drill through to add his own mount points, but of course popping holes in a modern PCB can be risky business. There’s not a lot of wiggle room between success and heartbreak, and it’s not like the diminutive D1 Mini is that easy to hold down to begin with. So he designed a laser-cut jig to allow him to rapidly add mounting holes to his D1 Mini’s assembly line style.

For those who might be skeptical, [Martin] reports he’s seen no adverse effects from drilling through the board, though does admit it’s possible the close proximity of the metal screw heads to the ESP8266’s antenna may have a detrimental effect. That said, he’s tested them in his projects out to 25 m (82 feet) with no obvious problems. He’s using a 2 mm drill bit to make his hole, and M2 x 6 mm machine screws to hold the boards down.

The jig design is released as a SVG and DXF for anyone with a laser cutter to replicate, but it shouldn’t be too difficult to extrude those designs in the Z dimension for hackers who haven’t yet jumped on the subtractive manufacturing bandwagon.

When a project makes the leap from prototype to in-house production, designing and building jigs become an essential skill. From flashing firmware to doing final checkout, the time and effort spent building a jig early on will pay for itself quickly in production.