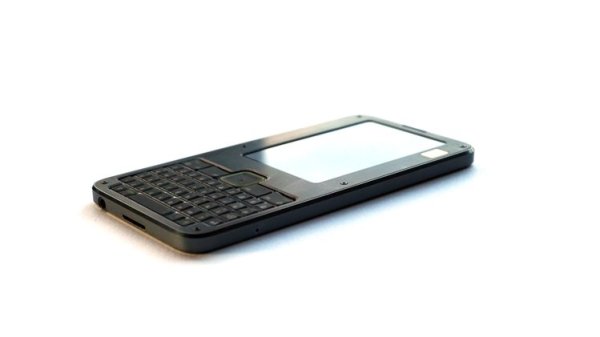

[Andrew] from [Wizard Keyboards] emailed us and asked if we were interested in his story of developing an ergonomic keyboard as a product. Many of us can relate to trying to bring one of our ideas to market. [Andrew], being a mechanical keyboard geek, knew a niche with no product to satisfy it, and had a vision he wanted to implement. He started meticulously going through steps for bringing his keyboard idea into life as a manufacturable product, and gave himself six months to get it done.

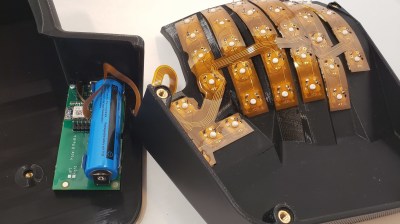

After evaluating competing products and setting a price point, he designed the case, the keyboard’s mainboard, and even flexible circuit boards for wiring the keys up. The mechanical design alone had him go through many iterations and decisions, and he walks us through the different paths he’s faced. Whether it’s these insights, a story of a module with fraudulent FCC certification, or an approach to electronics design that led to him passing EMC tests with flying colors, there’s plenty to learn from [Andrew]’s journey.

Sadly, at some point, the project quickly outgrew the intended goal and became a drain. For instance, tuning the 3D printing processes alone took three months instead of one as planned. As the design was done, he got stuck on marketing material production – a field that turned out to be unexpectedly hostile to a hacker like him. After a year of work and five thousand hours of work spent on the project, he took a break, and afterwards, as he was trying to come back, [Andrew] realized that he has burned out. He took a few month long hiatus, and having recovered a bit, revisited the project. Still not thrilled about the product route, he decided that open-sourcing the keyboard would be the best outcome – doing justice to the time and effort spent working on it.

This is where the story ends – for now. [Andrew] has open-sourced everything one would need to create such a keyboard by yourself, designed assembly instructions, and even sells kit parts for those who’d like to take a shortcut. This wasn’t what he aimed for, but it’s a honorable ending – most commercial projects never get open-sourced even if they utterly fail to launch. Thanks to [Andrew], we got an insightful journey, a postmortem, and an open-source ergonomic keyboard project. Product stories grace our pages every now and then – here’s a similarly swerving story about a MIDI controller.